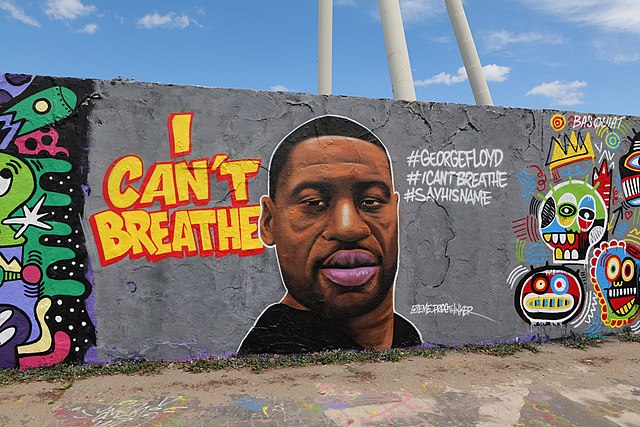

The murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man who was killed by a White police officer, affected the mental well-being of many Americans. The effects were multifaceted as it was an act of police brutality and example of systemic racism that occurred during the uncertainty of a global pandemic, creating an even more complex dynamic and emotional response.

Because poor mental health can lead to a myriad of additional ailments, including poor physical health, inability to hold a job and an overall decrease in quality of life, it is important to understand how certain events affect it. This is especially critical when the emotional burden of these events falls most on demographics affected by systemic racism. However, unlike physical health, mental health is challenging to characterize and measure, and thus, population-level data on mental health has been limited.

To better understand patterns of mental health on a population scale, Penn Engineers Lyle H. Ungar, Professor of Computer and Information Science (CIS), and Sharath Chandra Guntuku, Research Assistant Professor in CIS, take a computational approach to this challenge. Drawing on large-scale surveys as well as language analysis in social media through their work with the World Well-Being Project, they have developed visualizations of these patterns across the U.S.

Their latest study involves tracking changes in emotional and mental health following George Floyd’s murder. Combining polling data from the U.S. Census and Gallup, Guntuku, Ungar and colleagues have shown that Floyd’s murder spiked a wave of unprecedented sadness and anger across the U.S. population, the largest since relevant data began being recorded in 2009.

Their analysis further broke down this survey data along racial and geographic lines, showing a significantly larger effect among certain groups. The researchers found that nearly 30 percent of all Black respondents would have screened positive for depression in the week after Floyd’s death, up 3.2 percentage points from the prior weeks. In contrast, positive screens for depression rose 1.2 percentage points in White respondents.

“In screenings of over 900,000 individuals in the week following Floyd’s death, the increase in depression among Black Americans relative to White Americans corresponds to an additional burden of 2.7 to 6.3 million mentally unhealthy days,” says Guntuku.

Collaborating with Stanford Psychology Professors Johannes Eichstaedt and Steven Roberts, as well as Garrick Sherman, data scientist for the World Well-Being Project, Salvatore Giorgi, a graduate student in Ungar’s lab, and Megan Reynolds, a research coordinator at Stanford, the team published their study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

According to the Gallup COVID-19 Panel survey of 47,355 participants, all demographics showed a significant increase in feelings of anger and sadness a week after the murder of George Floyd.

“We looked at available data from Gallup between 2009 and 2016 and the mean weekly levels for anger and sadness were 14 percent and 17 percent, respectively,” says Guntuku. The highest anger and sadness levels reported following a violent event in that timeframe was the week after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School with over 16 percent reporting feeling angry and 22 percent reporting feeling sad. “In contrast, among the U.S. population in the week following George Floyd’s death, anger and sadness increased to over 38 percent.”

Unsurprisingly, this data showed that feelings of anger and sadness occurred more frequently in Black Americans than in White Americans; almost half (47 percent) of all Black Americans in the survey reported these emotions.

Additionally, depression and anxiety, already at high levels due to COVID-19, rose to their highest in the history of the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey a week after the murder. This data also showed that while depression and anxiety were significantly higher for both White and Black Americans, the impact was three times higher for Black Americans.

“It is indeed obvious that Black Americans felt more anger and sadness than White Americans after George Floyd’s murder,” says Ungar. “What wasn’t obvious before this study was how much more anger and sadness they had experienced.”

While survey data that shows this disproportionate impact may not be surprising, the survey questions were designed in a way that allowed researchers to quantify the toll of this event, which proved to be shockingly high.

“This has several downstream effects on individuals’ physical health, social and professional life, and family and personal wealth, and it emphasizes the need for intersectional research on race and health,” says Guntuku.

The team also examined the variable of proximity as an influencing factor on the mental-health impact of George Floyd’s murder. Data from both surveys showed that participants in Minnesota reported higher accounts of depression and anxiety when compared to other states.

“The murder had a larger effect on people who were physically closer or who identified more with the victim,” Ungar says. “Still, that burden in terms of mental health was more than we expected. I think that quantifying that cost is the main contribution of this paper.”

Beyond demonstrating the applications of computational approaches to mental health tracking, this study emphasizes the need to reflect on the racial inequality of these traumatic events and their aftermath.