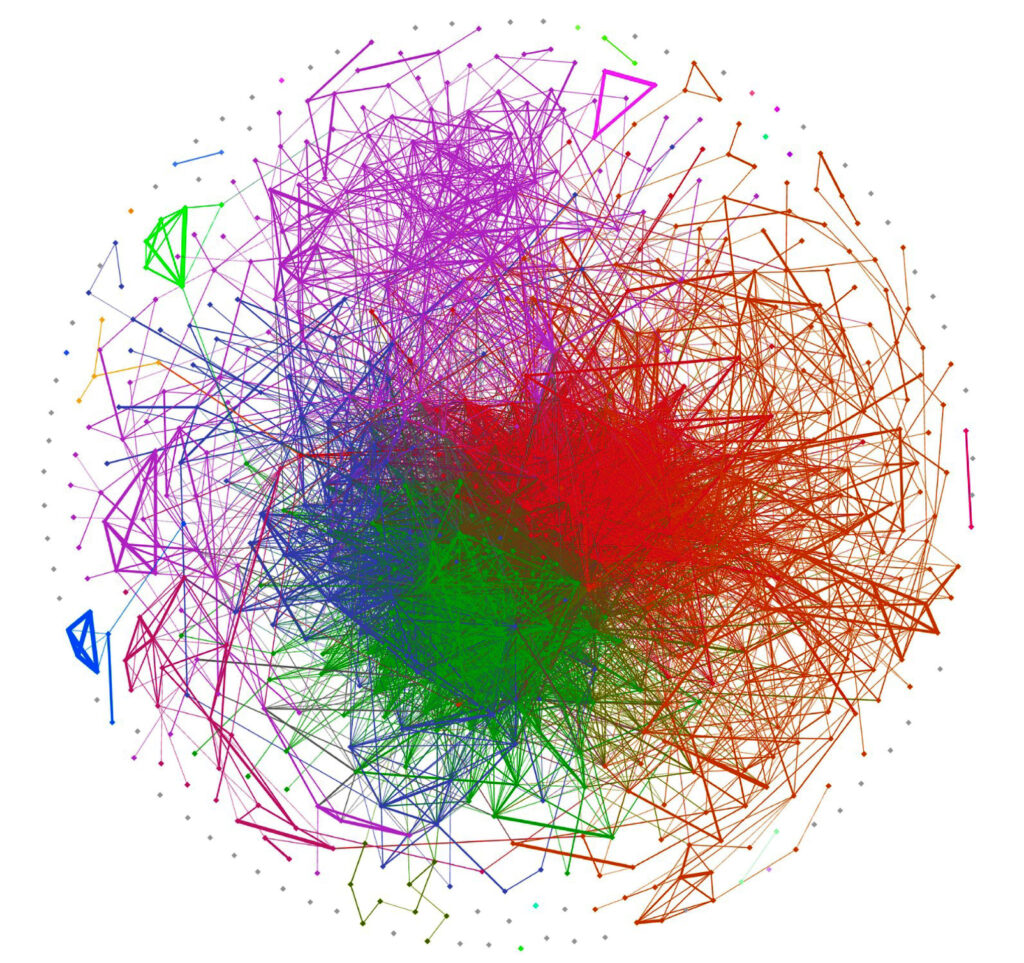

The network visualization depicting Kamen’s idea-generating process. Dots represent words that shaped Kamen’s artistic journey, lines indicate similarities between words, and colors represent communities of like ideas. (Image: Dale Zhou)

Communicating thoughts with words is considered a uniquely human evolutionary adaptation known as language processing. Fundamentally, it is an information exchange, a lot like data transfer between devices, but one riddled with discrete layers of complexity, as the ways in which our brains interpret and express ideas differ from person to person.

Learning challenges such as dyslexia are underpinned by these differences in language processing and can be characterized by difficulty learning and decoding information from writ

Artist-in-residence in Penn’s Department of Physics and Astronomy Rebecca Kamen has explored her personal relationship with dyslexia and information exchange to produce works that reflect elements of both her creative process and understanding of language. Kamen unveiled her latest exhibit at Arion Press Gallery in San Francisco, where nine artists with dyslexia were invited to produce imaginative interpretations of learning and experiencing language.

The artists were presented with several prompts in varying formats, including books, words, poems, quotes, articles, and even a single letter, and tasked with creating a dyslexic dictionary: an exploration of the ways in which their dyslexia empowered them to engage in information exchange in unique ways.

Undiagnosed dyslexia

“[For the exhibit], each artist selected a word representing the way they learn, and mine was ‘lens,’” explains Kamen. “It’s a word that captures how being dyslexic provides me with a unique perspective for viewing and interacting with the world.”

From an early age, Kamen enjoyed learning about the natural sciences and was excited about the process of discovery. She struggled, however, with reading at school, which initially presented an obstacle to achieving her dreams of becoming a teacher. “I had a difficult time getting into college,” says Kamen. “When I graduated high school, the word ‘dyslexia’ didn’t really exist, so I assumed everyone struggled with reading.”

Kamen was diagnosed with dyslexia well into her tenure as a professor. “Most dyslexic people face challenges that may go unnoticed by others,” she says, “but they usually find creative ways to overcome them.”

This perspective on seeing and experiencing the world through the lens of dyslexia not only informed Kamen’s latest work for the exhibition “Dyslexic Dictionary,” but also showcased her background in merging art and science. For decades, Kamen’s work has investigated the intersection of the two, creating distinct ways of exploring new relationships and similarities.

“Artists and scientists are curious creatures always looking for patterns,” explains Kamen. “And that’s because patterns communicate larger insights about the world around us.”

Creativity and curiosity

This idea of curiosity and the patterns its neural representations could generate motivated “Reveal: The Art of Reimagining Scientific Discovery,” Kamen’s previous exhibit, which was inspired by the work of Dani Smith Bassett, J. Peter Skirkanich Professor in Bioengineering and in Electrical and Systems Engineering at Penn Engineering, David Lydon-Staley, Assistant Professor of Communication at Penn and Perry Zurn, Associate Professor of Philosophy at American University on the psychological and historical-philosophical basis of curiosity.

The researchers studied different information-seeking approaches by monitoring how participants explore Wikipedia pages and categorically related these to two ideas rooted in philosophical understandings of learning: a “busybody,” who typically jumps between diverse ideas and collects loosely connected information; and a more purpose-driven “hunter,” who systematically ties in closely related concepts to fill their knowledge gaps.

They used these classifications to inform their computational model, the knowledge network. This uses text and context to determine the degree of relatedness between the Wikipedia pages and their content—represented by dots connected with lines of varying thickness to illustrate the strength of association.

In an adaption of the knowledge network, Kamen was classified as a dancer, an archetype elaborated on in an accompanying review paper by Dale Zhou, a Ph.D. candidate in Bassett’s Complex Systems Lab, who had also collaborated with Kamen on “Reveal.”

“The dancer can be described as an individual that breaks away from the traditional pathways of investigation,” says Zhou. “Someone who takes leaps of creative imagination and in the process, produces new concepts and radically remodels knowledge networks.”

The artwork Kamen produced for “Dyslexic Dictionary” harkens back to “Reveal.” The knowledge network provided a way to depict Kamen’s distinct way of processing verbal information by analyzing transcripts of researcher interviews to construct a dataset of the keywords Kamen said.

From those interviews, Zhou mapped out the relatedness between each topic and clustered similar words together, graphically representing Kamen’s information-seeking and idea-generation process.

Zhou notes that, “the distance between the dots here shows how Rebecca’s able to bridge dissimilar ideas.” Kamen calls that, “one of the gifts of dyslexia that I’m learning to appreciate.”

Kamen took Zhou’s visualization and affixed several of her artworks to a few nodes, relating the keywords she had used in the interviews to recognizable images.

This story is by Nathi Magubane. Read more about “Through the Lens: A Digital Depiction of Dyslexia” at Penn Today.