The Human Driver

As the ability to harness the power of artificial intelligence grows, so does the need to consider the difficult decisions and trade-offs humans make about privacy, bias, ethics, and safety.

By Gwyneth K. Shaw

As artificial intelligence has moved from the realm of science fiction into everyday applications, the thrilling possibilities — and the potential for problems — have drawn most of the interest.

Already, some AI-enabled practices have raised serious concerns, like the ability to create deepfake videos to put words in someone’s mouth, or the growing use of facial recognition technology in public places. Automated results that turned out to reflect racial or gender bias has prompted some to say the programs themselves are racist.

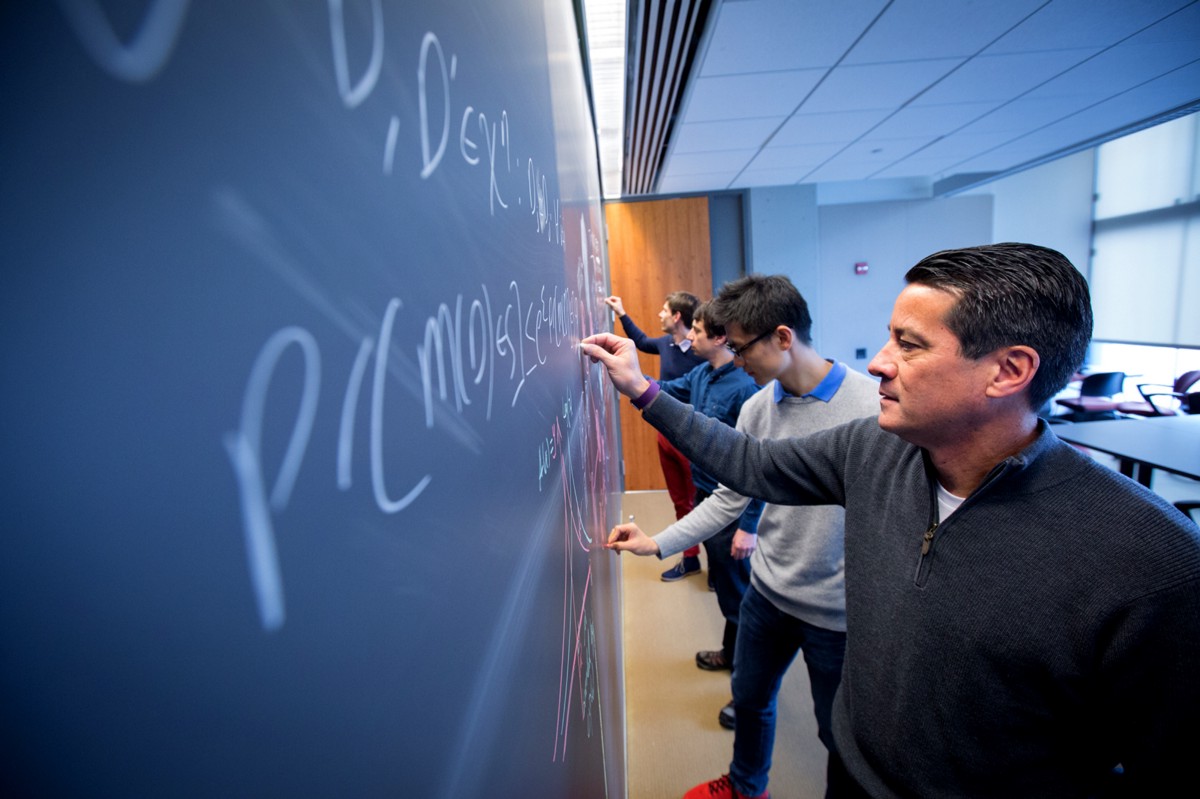

But the problem is more accidental than malicious, says Penn computer scientist Aaron Roth. An algorithm is a tool, like a hammer — but while it would make no sense to talk about an “ethical” hammer, it’s possible to make an algorithm better through more thoughtful design.

“It wouldn’t be a moral failure of the hammer if I used it to hit someone. The ethical lapse would be my own,” he says. “But the harms that algorithms ultimately do are several degrees removed from the human beings, the engineers, who are designing them.”

Roth and other experts acknowledge it’s a huge challenge to push humans to train the machines to emphasize fairness, privacy, and safety. Already, experts across disciplines, from engineering and computer science to philosophy and sociology, are working to translate vague social norms about fairness, privacy, and more into practical instructions for the computer programs. That means asking some hard questions, Roth says.

“Of course, regulation and legal approaches have an important role to play, but I think that by themselves they are woefully insufficient,” says Roth, whose book, “The Ethical Algorithm,” with Penn colleague Michael Kearns will be published in November.

The sheer size of the data sets can make transparency difficult, he adds, while at the same time revealing errors more easily.

“These aren’t new issues. It’s just that it’s sort of easy to ignore them when humans are making the decisions,” he says.

Continue reading at Penn Today. This story is part of Penn Today’s series on artificial intelligence.