Penn Engineers’ Network Analysis Uncovers New Evidence of Collaboration in Shakespeare’s Plays

The question of whether William Shakespeare truly wrote every word in every scene of his plays has been circulating since the time of The Bard himself. Wilder conspiracy theories posit that the playwright never truly existed, or was only an actor and not a playwright, but the consensus debate among literary scholars is over which plays might have been co-written — and who those unaccredited co-authors might be.

Information scientists at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, working with a Shakespeare scholar at De Montfort University, are using a new statistical method to get to the bottom of this question.

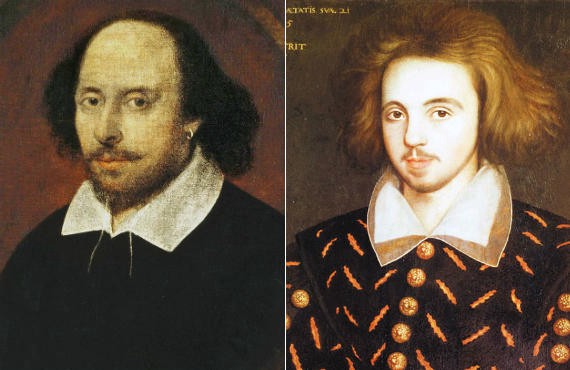

In a forthcoming essay for the Folger Shakespeare Library’s scholarly journal, Shakespeare Quarterly, they provide new evidence that all three Henry VI plays contain language written by another author. Their analysis identifies Christopher Marlowe as the likeliest candidate, although other writers may have been involved as well.

One thing is certain: Shakespeare did not write these plays on his own.

The study was conducted by Alejandro Ribeiro, Rosenbluth Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical and Systems Engineering, lab members Santiago Segarra and Mark Eisen, and Gabriel Egan, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at De Montfort University and one of the editors of the New Oxford Shakespeare Complete Works. Segarra is now a postdoctoral associate at MIT.

Even prior to the advent of computers, literary scholars have attempted to quantify an author’s style in efforts to resolve attribution questions. However, the rigor of available techniques — which often involved manual counting — was disputed. Computational approaches reinvigorated the field with the promise of increased reliability and objectivity.

“Using information sciences to answer questions about disputed authorship goes back two decades,” Ribeiro said, “and it has grown along with computing power. But our approach is more than just counting.”

Earlier computational approaches have tried to quantify authorial style through vocabulary and usage. Counting the frequency of certain words and comparing them across texts, were used to create profiles of authors’ vocabularies. However, this approach has a flaw — the distribution of words used in a text could be more influenced by its subject than its author.

“A more reliable approach,” Segarra said, “is to use functional, rather than meaningful, words: ‘the,’ ‘and,’ ‘or,’ ‘to,’ and so on. Everyone has to use these words, so analyzing how they differ between authors gets closer to an objective measure of ‘style.’”

Rather than simply counting the frequency of such words, the Penn team measured their proximity to one another. After constructing a list of between 50–100 functional words that appear in the target texts, the researchers apply an algorithm to derive “word adjacency networks” from them.

Each pair of functional words is given a score based on how many words apart they appear to one another. Together, those scores are remarkably consistent between different texts by the same author, acting as a kind of stylistic “fingerprint.”

“For example,” Ribeiro said, “If we trained this system on a play by me and a play by Santiago, and then gave it another play written by one of us, it could tell which one wrote it 98 percent of the time.”

Knowing the ongoing debates over Shakespearean authorship, the Penn team collaborated with Egan to ensure they were working within the confines of scholarly consensus. For example, one of Shakespeare’s later plays, The Two Noble Kinsmen, is now widely accepted to have been co-authored by John Fletcher. Some of his earlier works, such as the Henry VI plays and Titus Andronicus, were thought to be collaborations, but how much and with whom was less clear. This made them good targets for deeper analysis.

The researchers trained their algorithm on the entirety of Shakespeare’s corpus of plays, developing a stylistic fingerprint for him. They also developed fingerprints for several notable contemporaries, including Fletcher, Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Middleton, Ben Jonson, George Peele and others. Finally, they combined all of the texts from all of the candidates into a single profile, essentially an “average” fingerprint for English-language authors of that era.

The analysis of the word adjacency network fingerprints of the Shakespearean corpus suggested that the three Henry VI plays were stylistic outliers among Shakespeare’s plays. This anomaly made it very unlikely that these plays were written wholly by Shakespeare in its entirety, confirming results generated by other groups’ computational approaches.

“We’re seeing independent studies with different methodologies converging on the same conclusion,” Egan said.” “The more those independent approaches converge, the more confident we can be.”

Confident that the Henry VI plays were outliers, the next task was to see who else’s stylistic fingerprints they might contain. Christopher Marlowe and George Peele, long thought to have been the unnamed collaborators on Titus Andronicus, were the two leading candidates.

“If you had to pick one candidate, it would be Marlowe,” Segarra said. “If you had to pick two, then you would go for Marlowe and Peele, but in the latter’s case, we don’t have a large enough sample to fully train the classifier. Once you combine this with the historical evidence, Marlowe clearly becomes clearly the preferred coauthor.”

Egan is confident that the historical evidence tips the scales toward Marlowe. “Other investigators using entirely different approaches have recently uncovered evidence that makes Marlowe the prime candidate.”

“There’s a very famous riot scene in Henry VI, Part 2,” Egan said, “where one of the followers of Jack Cade, a revolutionary, says, ‘First thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.’ I think that Marlowe was responsible for the Jack Cade scenes. Of course, we don’t know if they sat together and worked as co-authors. Shakespeare may have adapted those passages afterwards, for example.”

Egan and his co-editors of the New Oxford Shakespeare Complete Works will identify Marlowe as Shakespeare’s co-author for all three of the Henry VI plays. The New Oxford Shakespeare, which contains versions of all Shakespeare’s writings in both modern and original spellings, plus analysis and commentary, is considered among the most authoritative scholarly resources on the playwright.

The findings are also a testament to the value of interdisciplinary collaboration.

“It’s fitting that this these questions about language are being tackled at the birthplace of computers, with ENIAC,” Egan said. “Language is the ultimate ‘big data’ problem, and attributing authorship to its rightful owners is both a technical challenge and, for editors, a moral obligation. It is fitting that a collaboration of twenty-first century writers from different backgrounds and with different but complementary skills should uncover a sixteenth-century collaboration that was likewise diverse in its origin.”