Machine Learning Detects Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Emoji Usage

By Lauren Salig

Emojis might be considered the digital extension of facial expressions, a universal form of communication that even infants can understand. However, while the idea of emojis unifying people across language barriers is enticing, people of different cultures might not use emojis in the same way.

In a recent study, Penn Engineers used machine learning to investigate similarities and differences in emoji usage in countries they defined as having either “Eastern” or “Western” cultures and what those differences might mean for how scientists view the relationship between online communication and health.

For example, when discussing health-related topics, the Western cultures tended to use more emojis with negative facial expressions than the Eastern cultures, which tended to use emojis representing healthcare-related objects, like a pill or hypodermic needle. An awareness that certain groups may put more emphasis on emotions and others on treatment logistics could be useful information for doctors or organizations that run health campaigns.

Lyle Ungar, professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science, and Sharath Chandra Guntuku, previously a postdoctoral researcher at Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering and currently a research scientist at Penn Medicine’s Center for Digital Health, led the research with Mingyang Li, then a graduate student in Penn Engineering’s MSE in Data Science program. Louis Tay, an associate professor at Purdue University, contributed to the study.

The paper was presented at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media in early June.

Ungar and his colleagues’ research aims to understand how people’s online language, images, and behavior relate to their mental and physical health. Their past research has looked at how the specific language people use in Facebook statuses or tweets correlates with later diagnoses of clinical depression. Extrapolating from those correlations, their work then attempts to predict the health of individuals from a broader audience.

“We’ve done a lot of work where we see people posting in a certain way or at a certain time of day and how that relates to their being depressed or anxious. We’ve also seen an association of emotions with health: people who express a lot of anger and negativity are more often depressed. This is well-researched in the United States,” says Guntuku. “But with many languages and diverse cultures, we want to start expanding that work.”

Emojis seemed a natural place to start exploring cultural influences on online communication. Since emojis are a form of emotional expression, they might help researchers determine which aspects of emotional communication are universal and which are culture-specific. This differentiation could provide insight into how correlations between communication and health may or may not hold true in other countries.

The researchers applied machine learning techniques to approach the cultural questions that Ungar says drove the study: “How do emojis reflect emotions? Is there universality in how emojis are used among cultures?” And, going forward, “How can we use those similarities and differences to better understand health?”

To begin addressing these questions, Ungar and Guntuku looked at how emojis were used on social media in countries that represented a sampling of Western culture — the United States, Canada, and the countries that make up the United Kingdom — and two countries that represented a sampling of Eastern culture — Japan and China.

Although each of these countries has their own unique culture, psychological research has long suggested some overarching differences in Eastern and Western cultures. For instance, countries of Eastern culture are often considered to put more value on family, while Western culture is thought to emphasize the individual more. The researchers wanted to start by looking at this class of larger cultural differences before future research narrows in on more specific cultural variations.

To study emoji usage in the US, Canada, the UK, and Japan, the researchers pulled 2014 data from an archive of Twitter data. For China, where Twitter is not widely accessible, the researchers looked at data from the social media platform Sina Weibo.

To analyze their sample of nearly one billion social media posts, the researchers employed programs that removed posts in languages other than the native language of interest for each country, converted traditional Mandarin characters to simplified Mandarin for easier translation, and broke the posts down into “tokens,” each of which consists of an individual word or emoji. From there, they could apply a machine learning method called vector embedding.

“With machine learning, we represent each token with a vector. The beauty of these vectors is that you can find associations between tokens and see how they are semantically similar to one another. A well-known example is that a vector of the token ‘king’ would be similar to a vector of ‘queen.’ If you do mathematical operations such as ‘king’ minus ‘man’ plus ‘woman,’ you get a vector close to that for ‘queen,’” says Guntuku. “We use these vectors to see how close each emoji is to words describing positive or negative emotions and to study associations between emojis and psycholinguistic categories like family, friends or death.”

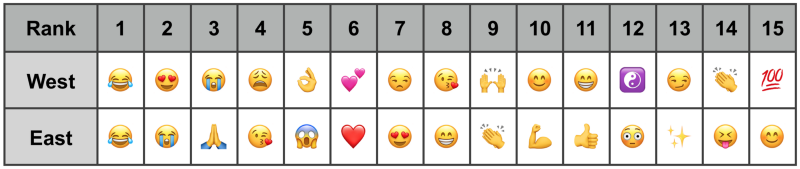

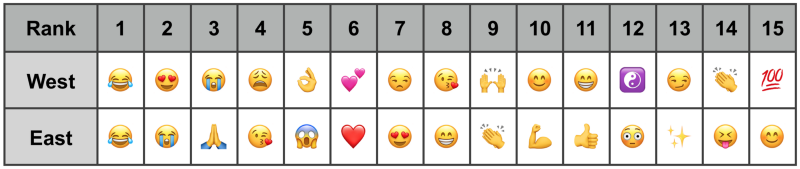

The researchers found that the similarities between Eastern and Western emoji usage far outweighed the differences. For the most part, the same emojis were used frequently in both culture groups, with different variations of facial expressions winning out as the most popular type of emoji, as compared to other types like emojis of food/drink or animals. However, when the team looked at how emojis were associated with certain topics, subtle variations emerged. While similar emojis were used together with topics like Death, Anger, Money and Home, the Eastern and Western cultures’ use of emojis differed for topics like Time, Friends and Work.

Guntuku believes that some of the differences in emoji usage come from larger cultural influences and some come directly from governmental policies:

“A lot of our Eastern data is from China, and if we look at emojis associated with Leisure in the East, we don’t see the gaming console because console gaming was banned in China until 2015. Whereas in the West, that’s one of the top associated emojis with Leisure. When we look at the category of Friends in the East, we see things like a policeman. In the West, one of the top emojis for Friends is drinking. In general, there is universality to emojis, but slight nuances like these can be captured using data like social media.”

This detailed look at a culture’s relationship with communication provides insight into how social media can and cannot speak to health in various communities. As future research attempts to make inferences about a general population’s health based on correlations with behavior on social media, it is important to understand what aspects of online communication reflect an individual’s health, what aspects reflect the culture they are immersed in, and how those factors interact. For now, the potential application of communication-health correlations to other countries seems possible in the future.

“Anger and anxiety are supposed to be universally expressed. That’s something we find even in emojis. This suggests that at least some of the online dimensions that are correlated with health, like Anger, might be more easily transferable across cultures, but some dimensions, like Family and Friends, that are also important in health, might be very different,” says Guntuku.

Although this study was exploratory and contains potentially confounding variables, like China’s censorship of online content, the researchers hope that it sets an important precedent for cross-cultural comparisons using social media data.

For those interested in delving deeper into this vein of research, the data and models used in this study are available on GitHub, and the researchers are interested in collaborating on future studies using longitudinal data collected from Sina Weibo.