In the early 20th century, as Isabel Wilkerson recounts in The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, millions of Black Americans left the South behind, fleeing the persecution of Jim Crow to search for a better life in cities like Chicago, New York and Los Angeles.

The family of Henry Coshburn (ChE’57) converged on New York’s Harlem from points north and south. His father’s ancestors traveled south from the shores of Lake Champlain, in upstate New York, while some of his mother’s forebears—including the religious leader and civil rights advocate William B. Derrick—emigrated from Antigua before settling in Flushing, Queens, while others traveled north from Virginia, where they had been enslaved.

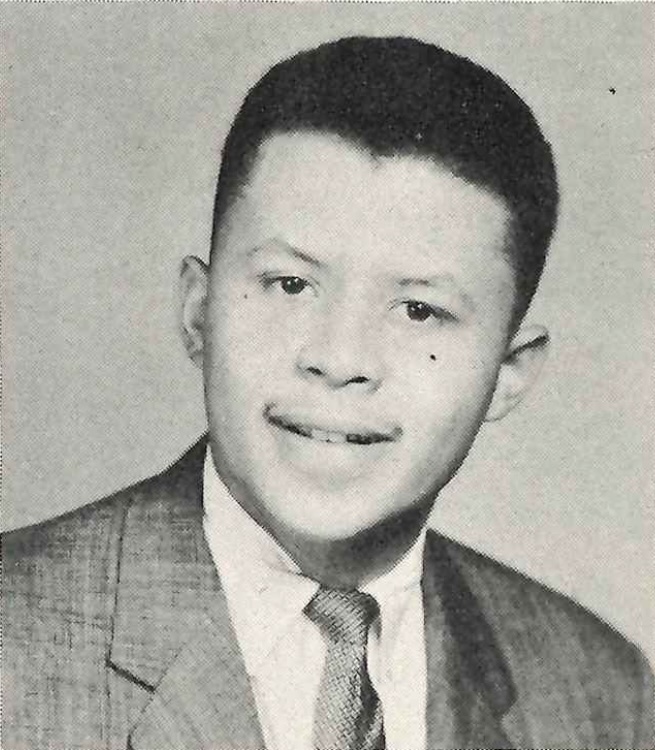

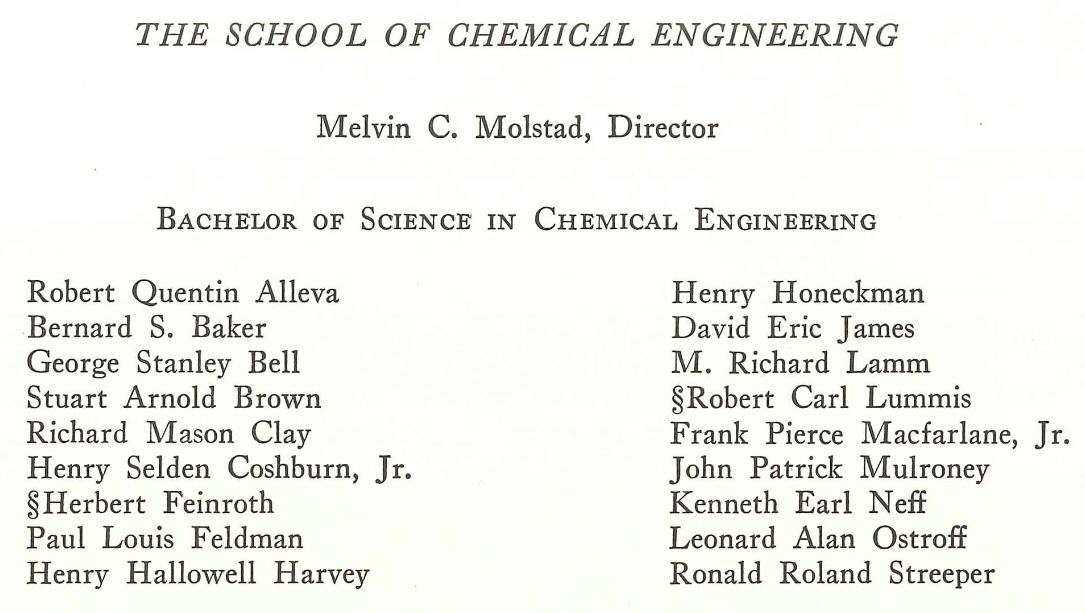

Coshburn grew up in Harlem just after the neighborhood transformed into the Mecca of Black America. From 1910 to 1930, the Black share of Harlem’s population rose from 10% to 70%, giving birth to the art, poetry and music of the Harlem Renaissance, and also to Coshburn, one of the first Black graduates of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Chemical Engineering.

Today, Coshburn, widowed after 50 years of marriage, still lives in New York City, in Riverdale, overlooking the confluence of the Hudson and East Rivers. His son, William, daughter-in-law and two grandchildren live just across the Hudson, in New Jersey.

As an engineer, Coshburn spent decades traveling the world, contributing to the development of batteries and industrial grease before becoming involved in the business side of the energy industry, where he marketed and brokered billions of dollars of petroleum transactions in international markets.

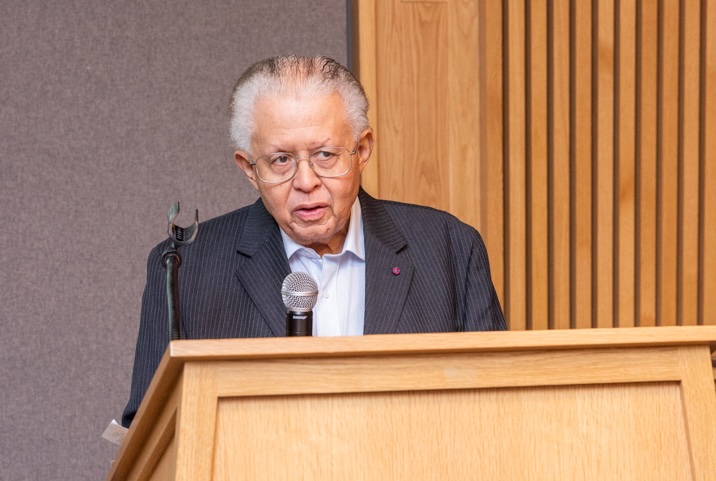

Recently, he returned to Philadelphia for the annual gala of the Penn Engineering chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE), where he received a lifetime achievement award, which has since been renamed in his honor. “Mr. Coshburn’s life story embodies what’s possible, especially for Black engineering students,” says Dr. Yulanda Essoka, Associate Director of the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Penn Engineering. “He supplies evidence that Blacks have been and can be successful in engineering, if given an opportunity, despite isolation and hostile climates. Ultimately, he exemplifies how all students can construct fulfilling personal and professional lives.”

Growing up in Harlem in the 1930s and 40s, Coshburn had little idea, at first, of how limited opportunities for Black Americans really were. “My friends and myself, we were somewhat naive,” Coshburn recalls. His mother, for instance, was college educated, making her an extreme outlier for the time—in 1940, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, the percentage of Black women with bachelor’s degrees was so low it went unrecorded.

In addition to observing the example of his family at home and in school—his mother taught at the public school he attended, and eventually became assistant principal—Coshburn also glimpsed life’s possibilities during services at St. Martin’s & St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

“The original rector was a Columbia graduate,” Coshburn says. “And he was the first Black on the Columbia basketball team. He was a basketball star in the 1920s. And I got to be pretty friendly with him.”

In fact, that rector, John Johnson, was one of the most recognizable and influential figures in Harlem, on par with Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the pastor who later became New York’s first Black Congressman. “Johnson played for the Harlem Rens,” recalls Coshburn—America’s first Black-owned, all-Black professional basketball team—and contributed to the integration of Major League Baseball, mentoring Jackie Robinson.

For Coshburn, in short, there was no lack of adults to ask about his direction in life. The rector’s son, David, a lawyer who attended Swarthmore and Columbia Law School, became a friend. “It was good seeing Blacks run a successful business,” says Coshburn. “When I had questions—and young people always ask questions—he was there.”

As a teenager, Coshburn imagined becoming a history teacher. But when his father, who served as an administrator in the public schools, expressed a less-than-rosy view of the profession’s financial prospects, Coshburn thought of one of his cousins, George Biddle Kelley, who had studied engineering at Cornell. Kelley, in fact, co-founded Alpha Phi Alpha, the nation’s first Black fraternity. “The next time my father asked me what I wanted to do,” Coshburn recalls, “I said I’d like to be an engineer.”

In school, Coshburn excelled in mathematics. “Math is kind of pure,” says Coshburn. “You don’t have to memorize it. You have to understand it.” He brought his aptitude for math and science to Dewitt Clinton High School, in The Bronx, only a decade or so after the writer James Baldwin graduated. Only a few years earlier, Clinton might have been the largest high school in the world, with 12,000 students. Coshburn nonetheless stood out. He was elected to the honors society, named co-captain of the senior-class basketball team and elected senior class president.

In 1953, when Coshburn enrolled at Penn, the civil rights movement was just beginning to take shape. “I was the only Black in the chemical engineering class,” Coshburn recalls. There were so few Black students at Penn that Coshburn would travel to Temple on the weekends to socialize. The following year, when Brown v. Board of Education officially desegregated the country’s public schools, more Black students arrived at Penn. The next year, even more.

Pretty soon, Coshburn didn’t need to travel off campus to socialize with other Black students. He met one of his first mentors, Al Bishop (ChE’50), who received a Ph.D. from Carnegie Mellon and later taught at the University of Pittsburgh, while rushing Alpha Phi Alpha, the Black fraternity. “He called me once a month,” says Coshburn. Bishop would even visit campus to check in on Coshburn, a practice that Coshburn later emulated with the students he mentored.

Coshburn and his classmates took full advantage of being in Philadelphia. The night before graduation, in 1957, Coshburn and his fellow Alpha Phi Alpha brother and close friend Westervelt K. “Kirk” Taylor (EE’57) found themselves in a nightclub on South Street, chatting with Billie Holliday. “She sat down at the table with us for half an hour,” Coshburn recalls.

It wasn’t until graduation that Coshburn encountered the full force of everything from which his parents had shielded him. Growing up, Coshburn didn’t know that, as preteens, his mother and her sister were denied entry into their Episcopal church’s Confirmation class, in Flushing, Queens, for being Black. He didn’t know that, after passing the exam for her teaching license, his mother had to travel two hours each way from Queens to Harlem not for a job, but for the possibility of temporary employment as a substitute teacher at the city’s only school with a Black principal. “My mother experienced a lot of prejudice at an early age,” Coshburn says. “She didn’t pass that along to us, and my father didn’t pass that along either.”

As a result, it came as something of a shock when the labor market completely ignored his chemical engineering degree. “I didn’t get any jobs,” Coshburn says. For the first two months after graduation, Coshburn delivered mail. Then he took an examination and qualified to become a lab instructor in the New York City public schools. For a time, he had to commute to Staten Island from Harlem, which took two hours each way, including four subway trains, one ferry ride, one bus ride and a half-mile walk.

He interviewed again with the class of 1958—same result. One company said, “We have a lot of plants in the South, and you can’t work in the plants in the South.” Coshburn pointed out that the company also had plants in Michigan, Indiana and New York. But the interview, like all the rest of them, went nowhere.

And then, by pure chance, Coshburn interviewed at one of the few American institutions legally prohibited from discriminating against Black applicants: the U.S. Army, which President Truman had officially desegregated in 1948.

Coshburn joined the Signal Corps, at Fort Monmouth, where he worked on batteries. “Back in those days,” Coshburn says, “no one cared about batteries.” Just as he would later, in the oil industry, Coshburn found himself on the frontier of a technology with unexplored potential. The specific technology on which he worked—rechargeable, solar-powered batteries for satellites—wouldn’t sound out of place today.

Two years later, in 1960, Coshburn moved into the private sector, working in sales for a battery company in New York that served the Army, Navy and Air Force. He then returned to school, at Columbia, for his master’s degree, also in chemical engineering, at which point President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which changed the employment landscape so drastically that Coshburn left graduate school with 18 different job offers.

Just a few years earlier, some of Coshburn’s parents’ friends suggested that he might have been better off never studying engineering in the first place. “They were inferring that it was my fault that I took chemical engineering,” he says. “And that society was not at fault for not hiring me.”

For the first time, Coshburn’s talents were recognized by the labor market. “I haven’t changed,” he recalls thinking. “I’m the same person who couldn’t find a job.” But, thanks to the civil rights movement, American society was starting to see more clearly who Henry Coshburn really was.

Traversing the New Jersey Turnpike between Philadelphia and New York City, Coshburn often passed the byzantine pipes of the Bayway Refinery, at the juncture of Linden and Elizabeth, New Jersey. “I saw these towers and lights up there,” Coshburn remembers thinking, “and I said, ‘That’s pretty interesting.’”

To secure a foothold in the petroleum industry, Coshburn took a job at what was then Mobil Oil, where he was soon promoted to senior engineer. One of the first problems he focused on was developing a grease that didn’t liquefy at high temperatures so it could be applied to cars early in a production line and withstand the temperature flux of the manufacturing process.

Before long, Coshburn had a patent to his name, and the attention of his superiors. They wanted to send him to a refinery in Beaumont, Texas, that was having a problem producing industrial lubricants. “We’re not sure how this is going to work,” his boss told him. The Beaumont refinery, it turned out, was still segregated.

For Coshburn, the hazards of working in the oil industry were readily apparent. “I was going to be the first Black who was going into the Beaumont refinery to give orders to people,” Coshburn says. His supervisor would travel with him; in case Coshburn couldn’t stay at a local hotel, they would arrange to stay with a company executive.

And then there was being in the plant itself. “Working in grease is like working in the steel industry,” says Coshburn. “You have a 20,000-lb kettle. And you heat this kettle up to 250°F and you’re on platforms and you’re working over these kettles. Now, if someone wants to push you into those kettles, you’re dead. They’re not going to pull you out.”

Fortunately, the trip went off without incident. The foreman wound up giving Coshburn a hug. “We work well together,” the foreman said. “And you come back anytime that you want.”

Still, as soon as Coshburn had the chance to never work in East Texas again, he took it. After an interview at Rockefeller Center, he moved to Esso Eastern, which focused on markets like the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. “There was a lot of prejudice within the Gulf Coast,” says Coshburn.

The new job also let him transition from the technical side of the energy industry to the business side. “This was the marriage, to me, of history, which my father didn’t want me to do,” says Coshburn, “and engineering, because the engineering degree was the entry into the business—all the people that you were dealing with, whether it was in France, whether it was in Germany, Russia or Slovakia, they had an engineering degree or they had a chemistry degree.”

The transition wasn’t entirely without hiccups. Before realizing that English common law governed international business, Coshburn drafted a contract for two German companies that stipulated the deal would fall under German law. “I got two urgent phone calls,” Coshburn recalls—one from each party, as soon as their offices opened in Germany, at 3 a.m. on the East Coast.

Still, because he spoke the language of engineering, Coshburn soon found himself a capable negotiator, able to simultaneously evaluate the technical merits of deals and take into account the intricacies of doing business across borders.

Even after striking out on his own, his reputation followed him. Once, in Rome, he had dinner with half a dozen Italian petroleum industry executives. Why, Coshburn wanted to know, did they treat him just as nicely as when he worked for the world’s largest petroleum company? The executives looked nonplussed. In a sense, they had never done business with those companies—they had done business with Coshburn.

In the years since, Coshburn has entered the business of giving back. A 35-year board member of the Harlem Hospital, 1987 Penn Alumni Award of Merit winner and mentor to countless Black engineers, Coshburn has made it his mission to increase opportunities for underrepresented minorities in engineering.

The list of his contributions to the engineering community, both at Penn and beyond, is literally decades long.

Beginning just a few years after his own graduation, Coshburn started routinely visiting campus to mentor Black engineering students at Penn, just as his mentor Al Bishop had checked in on him. “I had a strong feeling that you just don’t put kids on the campus—that you follow up,” says Coshburn.

For years, Coshburn represented Penn at high-school college nights. He also spoke at historically black colleges and universities throughout the United States and secured internships for countless students. When students at Southern University, in Baton Rouge, asked him about opportunities at the Exxon refinery in town, Coshburn called the firm’s New York office, and immediately set up a tour.

In addition to mentoring and supporting minority engineering students at Penn, where he returns every year for the annual Penn NSBE gala, Coshburn has devoted himself to advancing the interests of minority high school students with a yen for math and science.

In the 1970s, he started a volunteer tutoring network in New York City, which brought professional engineers into the classrooms of Dewitt Clinton and Taft High School, in the Bronx, and the High School of Commerce and Benjamin Franklin High School, in Manhattan. In addition to Saturday morning tutoring sessions, the program partnered with the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and Exxon to sponsor educational trips to the Bayway Refinery, in New Jersey.

What’s more, Coshburn has philanthropically supported Penn Engineering. At the Penn Club of New York, where he served as vice president for a time, Coshburn once overheard a conversation in which someone suggested that minority students would be unlikely to donate to their alma mater—so he volunteered as a fundraiser for his class.

To Dr. Laura Stubbs, Senior Director of the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, the power of Coshburn’s example can be seen in the number of Black alumni who credit him as a mentor. “Don Maynard and Charles (Chuck) Wardlaw, who co-founded Penn NSBE, constantly give credit to Henry Coshburn, a fellow Chemical Engineering graduate, as a role model and mentor to them,” she says.

The fact that Coshburn has been included not just in the Marquis’ Who’s Who in Science and Engineering but the Who’s Who Among Black Americans, speaks to his dual achievements, as both an engineer and an advocate for the Black community.

At this year’s NSBE gala, Coshburn exhorted the newest cohort of Black engineers not to forget their responsibility to the next generation. “You have to mentor,” he said. “You have to reach back.”

To support the work of the Penn Engineering Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, give to the Cora Ingrum Fund, named for ODEI’s founding employee and longtime champion.