“What do you remember about stress and strain?” Max Lawrence, who teaches engineering at Science Leadership Academy at Beeber, a public middle and high school in West Philadelphia, paces energetically, gesturing at a complicated graph projected on the whiteboard.

His seniors raise their hands in rapid succession. They throw out words like density and force. Lawrence shakes his head. “You guys are using all these fancy words because you don’t actually understand the concepts yet.”

The graph is a stress/strain curve, a classic concept in engineering that shows how materials deform when you apply a load to them. “There’s actually a point where you stretch certain materials out and they become stronger,” says Lawrence, pointing to the curve’s irregular shape.

The concept is also a crucial element of the National Engineering NOCTI (National Occupational Competency Testing Institute) graduation exam. As members of a CTE (career and technical education) program, all of Lawrence’s students will need to pass the exam to receive the Pennsylvania Skills Certificate — and potentially earn advanced college credit.

The problem is that book learning can only take you so far. As Lawrence puts it, “I can tell them about stress and strain, but if they don’t do something with their hands they won’t remember it.”

Bringing Research Into the Classroom

The Center for Engineering MechanoBiology (CEMB), which brings together Penn, the National Science Foundation, the Franklin Institute and more than a half dozen other universities, exists in part to help STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) teachers like Lawrence. “Part of our mission has always been lifelong learning,” says Annie Jeong, the CEMB’s former managing director.

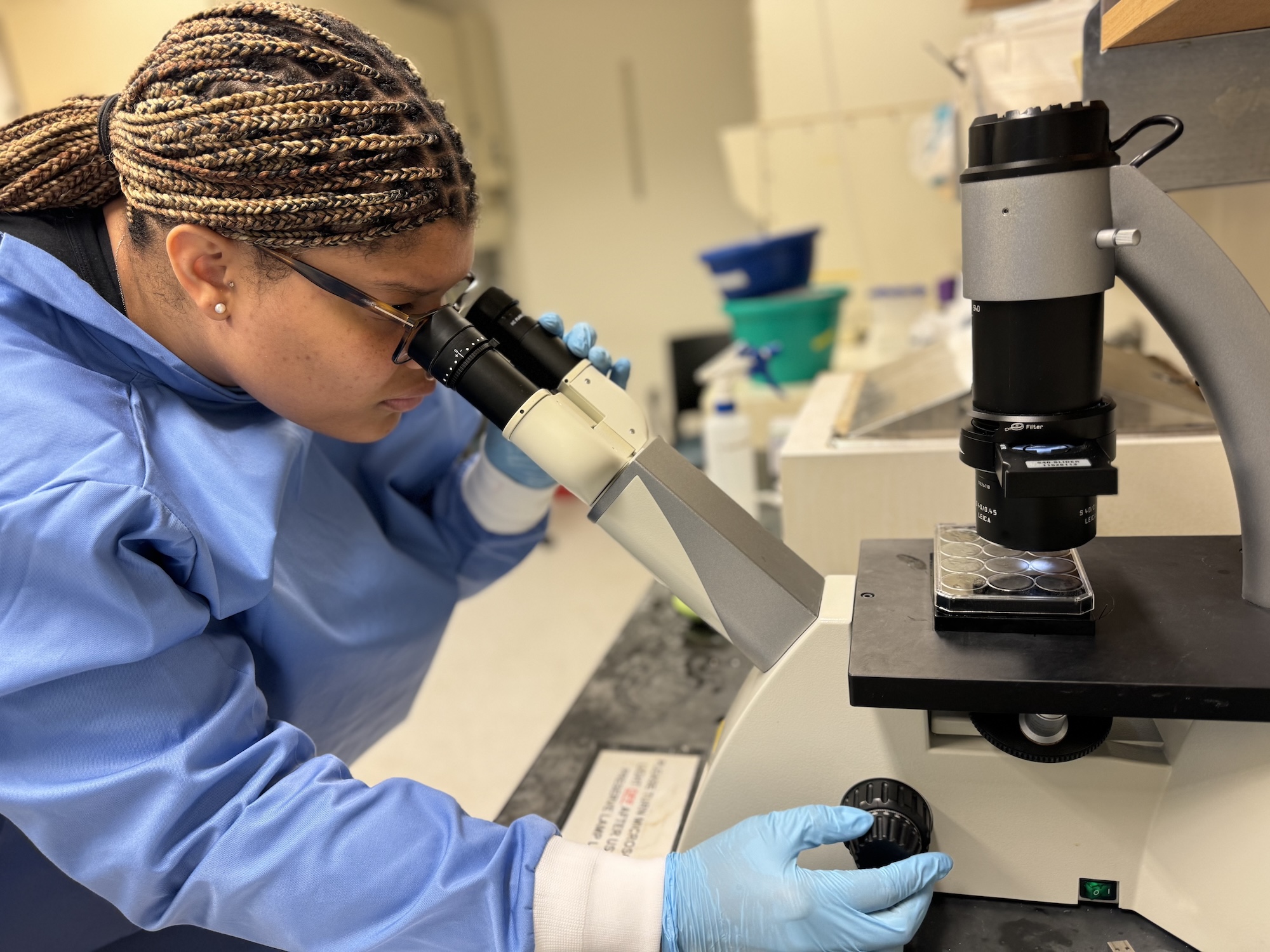

Founded in 2016 as an interdisciplinary hub for research and education, the CEMB offers K-12 teachers in Philadelphia a paid, six-week summer program to expose them to cutting-edge scientific research. The teachers then work with CEMB staff, scientists and engineers to develop innovative, hands-on lessons to engage students in STEM-integrated education.

“I saw this as an opportunity for me to come work and learn,” says Lawrence, who participated in the Research Experience for Teachers (RET) twice, most recently working with postdoctoral fellow David Li in the lab of Rebecca Wells, Co-Director of the CEMB and Professor of Gastroenterology and Hepatology in the Perelman School of Medicine. “I feel like I’ve had a private tutor now for two years.”

Breaking Down Silos in STEM

The traditional way to teach concepts like the stress/strain curve — or really any concept in math and science — is to divide ideas by discipline. Cells belong in biology. Stress and strain in physics. “We’re trying to bridge the gap between science courses in K-12 education and real-world research,” says Amanda Cottone, the CEMB’s Director of STEM Education, who directs the RET. “We want students to learn about careers and opportunities at the intersection of these fields that they otherwise wouldn’t have had exposure to.”

Mechanobiology is inherently interdisciplinary, a blend of biology, engineering, physics and chemistry that asks questions about how living things and physical forces intersect. One of the CEMB’s most popular curricular offerings involves learning about how Venus flytraps convert mechanical stimuli — like the pressure exerted by insects landing on them — into electrochemical activity.

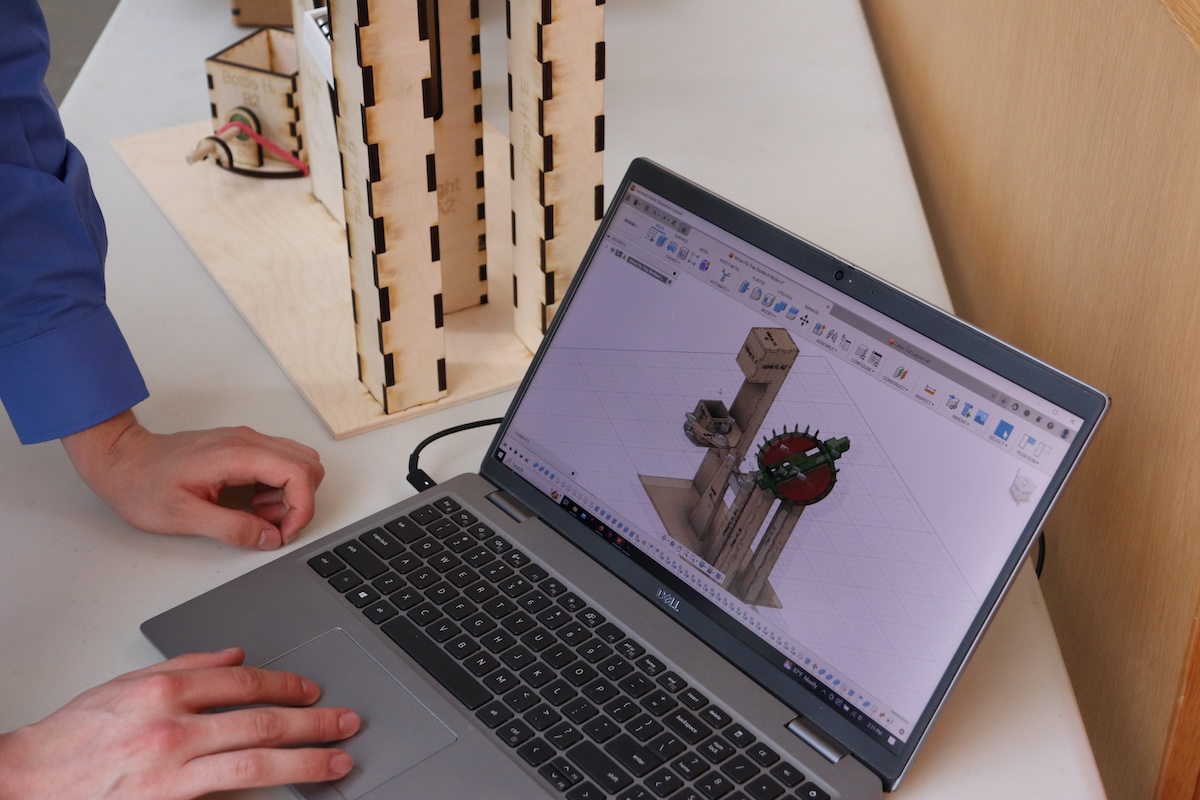

Developed jointly by Ryan McCarthy, Lawrence’s engineering assistant at SLA Beeber; Ezana Rivers, an undergraduate at West Chester University (WCU); her mentor, Michael Rosario, Assistant Professor of Biology at WCU; and Zoe Nguyen, a former master’s student at the Penn Graduate School of Education, the unit explores this concept from multiple angles.

In addition to building a physical flytrap model out of wood, water bottles and rubber bands, students also computationally simulate the voltage-gated ion channels of the cells that allow Venus flytraps to close, and learn how to measure the electrical activity in living plants.

“Most people have never heard of mechanobiology,” says Cottone, “but it’s all around us, from the way our cells divide to crucial indicators of health.”

Hands-On Learning in Action

Indeed, since ancient times, physicians have palpated — pressed with their fingers — the bodies of patients to probe for disease, mechanically searching for biochemical clues.

Starting in the late 1980s, researchers realized that sound waves could be used to take more accurate measurements. If they pinged an organ with an ultrasound, essentially pressing on it with tiny forces, they could measure the organ’s elasticity. This is especially helpful for monitoring the health of the liver. The scar tissue of cirrhosis stiffens the organ — an early indicator of the disease.

In the classroom, Lawrence introduces Ariel Parker, the CEMB’s Director of Partnerships and Legacy. A former student teacher at SLA Beeber, Parker created the course curriculum and has worked with Lawrence to develop lessons about mechanobiology — and reframe some of the dry, complicated charts they’ll see on the NOCTI exam.

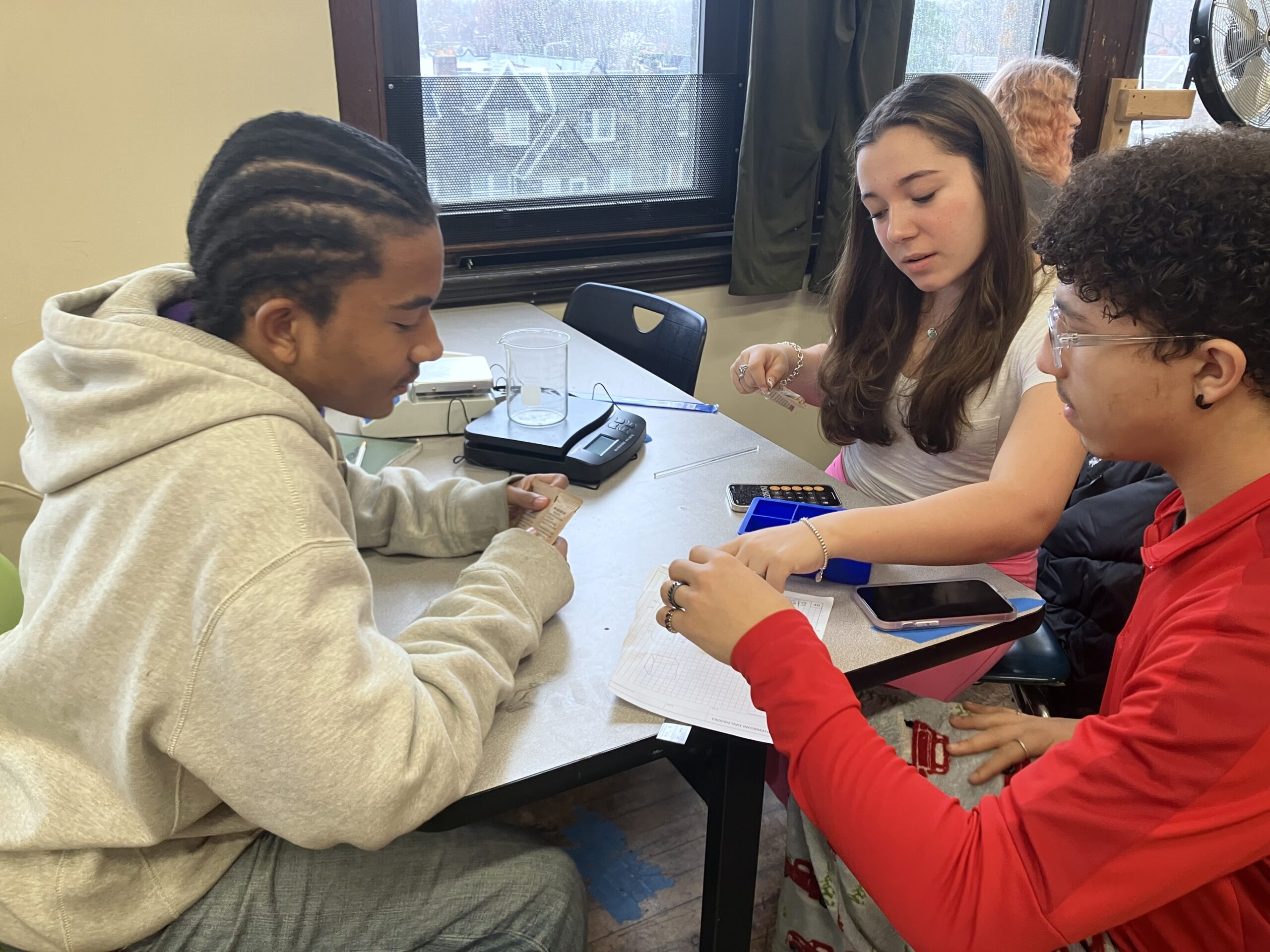

After Parker gives a brief lecture on the liver — how it works, what it does — Cottone talks the class through the experiment they’ll spend three days performing. Each group will make blocks of gelatin with a particular density, representing different samples of liver tissue. Once the gelatin has cured, they’ll measure the elasticity of each block, essentially deriving the chart on the board.

Lawrence sets the students off, leaving them to figure out how to combine the resources for the experiment — powdered gelatin, graduated cylinders, hotplates, cube-shaped silicone molds, water and electronic scales — to produce the liver facsimiles, which will then cure overnight.

“One of the things I hated about labs in school was how little thinking was involved,” says Lawrence. “I want my students to see that science requires engineering. How do we measure this? How can you do it consistently? How do you reproduce this?”

The students split up, some gathering supplies while others begin calculating the necessary ratio of gelatin to water for each block. It’s as if Lawrence has taken some of his own summer experience in the Wells Lab and brought it back to his classroom.

Building a Community of Educators

In addition to curriculum development, the CEMB’s summer program for teachers also provides community. Last summer, Lawrence partnered with Kayla Gay, who teaches math and science to sixth-graders at Cook-Wissahickon, a public elementary and middle school in northwest Philadelphia.

For Lawrence, who studied fine art, computer science and electrical engineering, having a partner with a different educational background proved extremely fruitful. “There’s a lot I don’t know about biology,” says Lawrence. “I was able to ask her questions to help fill in gaps in my understanding.”

Likewise, for Gay, having a partner with whom she could exchange ideas — about how to translate complex scientific content into grade-appropriate lesson plans— mattered just as much as getting to work alongside professional researchers. “When you think of the word ‘mechanobiology,’ it just sounds like this extreme, super-intense idea,” says Gay. “But when we broke it down, it definitely felt like I could teach my kids about it.”

Each week, Gay and Lawrence met up with the other teachers in the program, a mix of middle- and high-school teachers from across the city, to debrief their experiences and get to know each other. “In the lab, we were making hydrogels, learning photolithography,” recalls Gay. “But while we were doing the experiments, we were also figuring out ways to bring this back to our classrooms in a more concrete way.”

Empowering the Next Generation

For both Lawrence and Gay, the impact of participating in the CEMB’s summer program is apparent in their classrooms. “Kids love doing anything hands-on,” says Gay. “That I can go into a lab with other teachers, learn new concepts, get paid for it and then bring it back to my students — it’s like a win-win for everyone.”

Lawrence got so much out of his first year in the program that he came back for a second to continue conducting mechanobiology research and designing curriculum for his new high school course. “To have brand new curriculum on an interdisciplinary level, that has all the Next Generation Science Standards,” says Lawrence, referring to the Venus flytrap project and the liver elasticity experiment. “I wouldn’t have been able to do this without the CEMB.”

Philadelphia middle- and high-school teachers interested in the CEMB’s Summer Research Experience for Teachers (RET) Program, which takes place from June 23 to August 4, 2025, are encouraged to apply online by April 1, 2025.