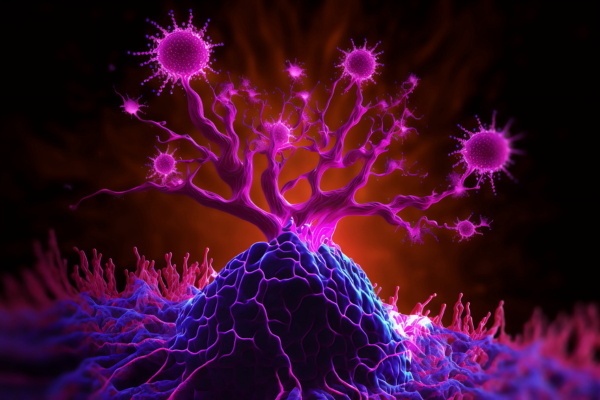

The tumor microenvironment—an ad hoc, messy amalgamation of signaling molecules, immune cells, fibroblasts, blood vessels, and the extracellular matrix—acts like a “powerful security system that protects solid tumors from invaders seeking to destroy them,” says Michael Mitchell, a bioengineer at the University of Pennsylvania working on nanoscale therapeutics aimed at targeting cancers.

“A lot like the Death Star with its surrounding fleet of fighter ships and protective shields, solid tumors can use features like immune cells and vasculature to exert force, acting as a physical barrier to rebel forces (nanoparticles) coming in to deliver the payload that destroys it,” Mitchell says.

Now, researchers in the Mitchell lab have teamed up with Wei Guo’s group in the School of Arts & Sciences at Penn and Drew Weissman of the Perelman School of Medicine to figure out the molecular mechanisms that make tumor microenvironments seemingly impenetrable and found that small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are secreted by tumor cells and act as a “forcefield,” blocking therapeutics. Their findings are published in Nature Materials.

“This discovery reveals how tumors create a robust defense system, making it challenging for nanoparticle-based therapies to reach and effectively target cancer cells,” Guo says. “By understanding the cellular mechanisms driving these responses, we can potentially develop strategies to disable this defense, allowing therapeutics to penetrate and attack the tumor more efficiently.”

The research builds on a prior collaboration between Guo and Mitchell’s labs, wherein the teams focused on how tumor-associated immune cells, known as macrophages, contribute to the suppression of anti-tumor immunity by secreting extracellular vesicles.

This story was written by Nathi Magubane. To read the full article, please visit Penn Today.