Penn Researchers Demonstrate How to Control Liquid Crystal Patterns

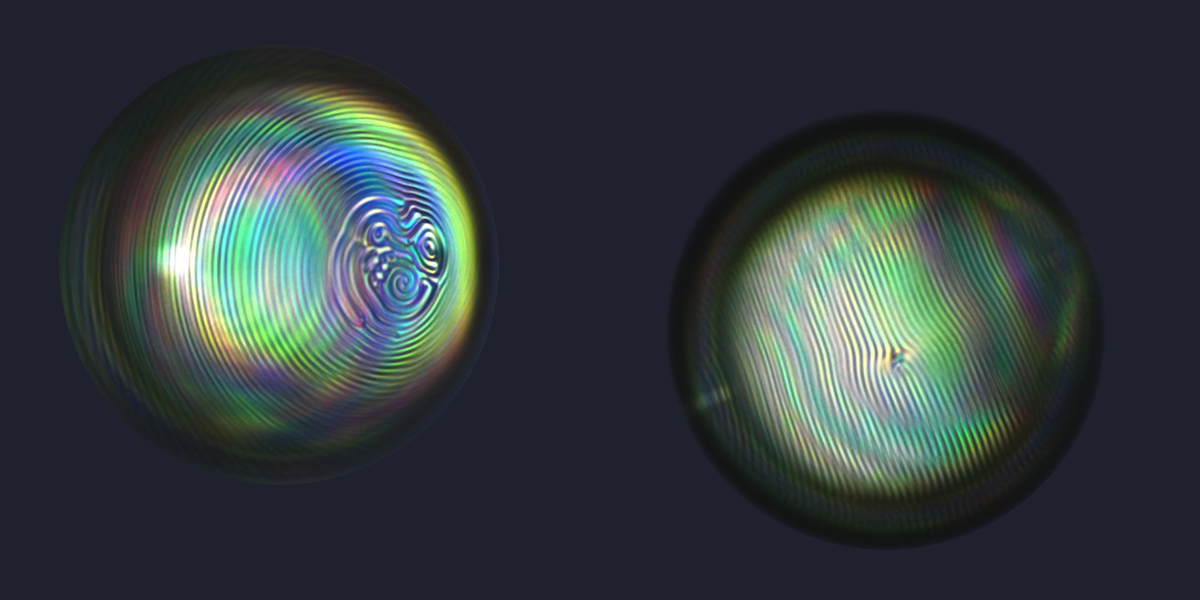

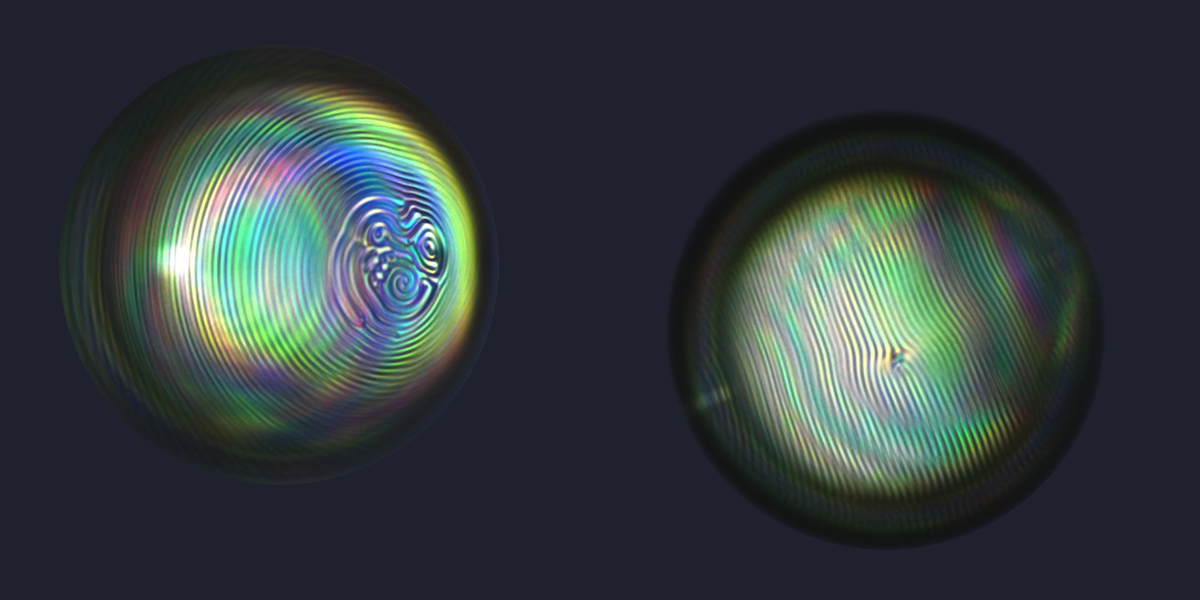

When Lisa Tran set out to investigate patterns in liquid crystals, she didn’t know what to expect. When she first looked through the microscope, she saw dancing iridescent spheres with fingerprint-like patterns etched into them that spiraled and flattened as the solution they were floated in changed.

The sight was so beautiful that Tran, a graduate student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Arts and Sciences, submitted a video of it to the Nikon Small World Competition and ended up winning fifth place. But the importance of the results stretch far beyond their aesthetic appeal, with possible applications in biosensing and energy harvesting.

Liquid crystals, fluids with aligned phases of constituent molecules, are used in everything from computer and television displays to mood rings. Since liquid crystals are made of rod-like molecules, they have special optical properties, such as changing color as they interact with electrical signals or light.

For this research, Tran confined the liquid crystals within droplets, creating shells floating in water. Tran and her advisor, Randall Kamien, the Vicki and William Abrams Professor in the Natural Sciences at Penn, described the droplets as “fancy bubbles.” To create patterns, Tran then added surfactants, or soapy molecules, to the water.

“The way that soap usually works,” Tran said, “is that you mix it with water and it forms small droplets with the oil to remove it from your hands or your plate.”

Because liquid crystals are similar to oil, the surfactants were attracted to the liquid crystal shells, causing the molecules to order in different ways and create striking patterns. The more soap she added to the solution, the more the patterns changed. Adding water caused the patterns to reverse.

Being able to control the patterns that form on the liquid crystals could be useful in creating patchy colloids, microscopic particles suspended in water that are functionalized, meaning one can attach molecules to specific spots on the particle.

“If you think about a ping pong ball, it’s completely uninteresting,” Kamien said. “But then you think about a golf ball, which is similar in size, but there are dimples on it. So the thing about Lisa’s work is that by controlling the patterns that you see optically, it physically textures the surface, which enables you to attach things to it at particular places.”

The paper, published in Physical Review X, was led by Tran and Kamien in collaboration with Kathleen Stebe, the Richer & Elizabeth Goodwin Professor, and professor Daeyeon Lee, in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science. They also collaborated with the group of Teresa López-León from the École Supérieure de Physique et de Chimie Industrielles de la Ville de Paris.

The research is a key component in one of the interdisciplinary research groups of Penn’s recent $22.6 million NSF Materials Research Science and Engineering Center grant. The group is working to make assemblies of nanocrystals on hard templates and within soft materials that hold promise for applications in sensing, energy conversion and optical-signal processing.

Continue reading on Penn News.