Machine Learning Researchers Try to Improve Working Conditions for Amazon’s Mechanical Turk Workers

By Lida Tunesi

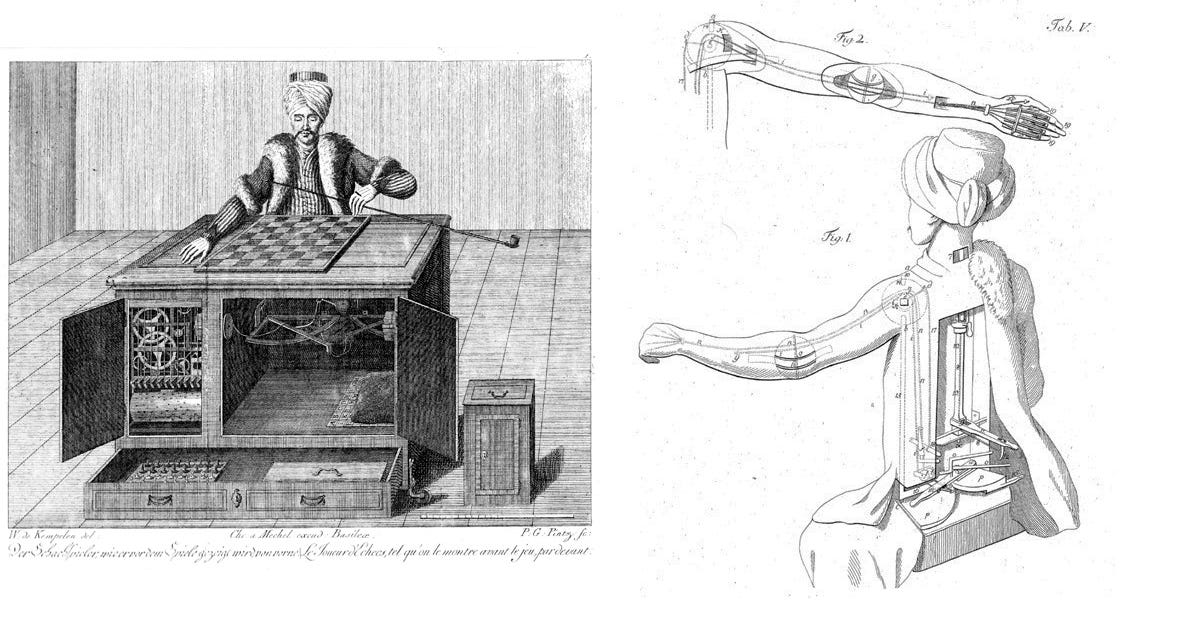

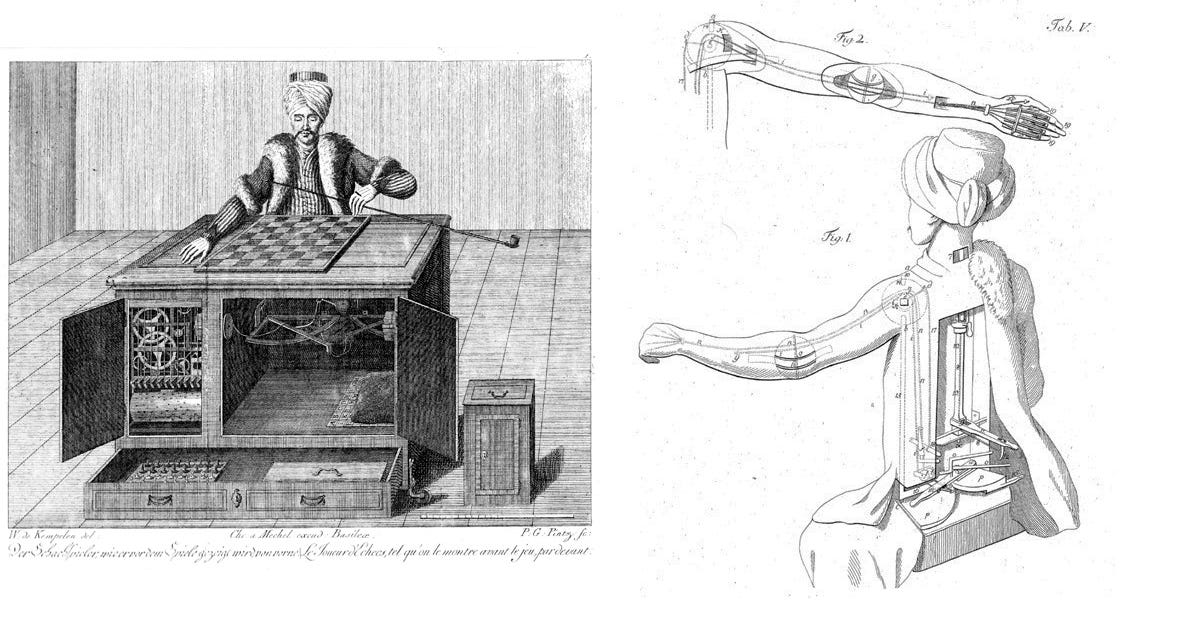

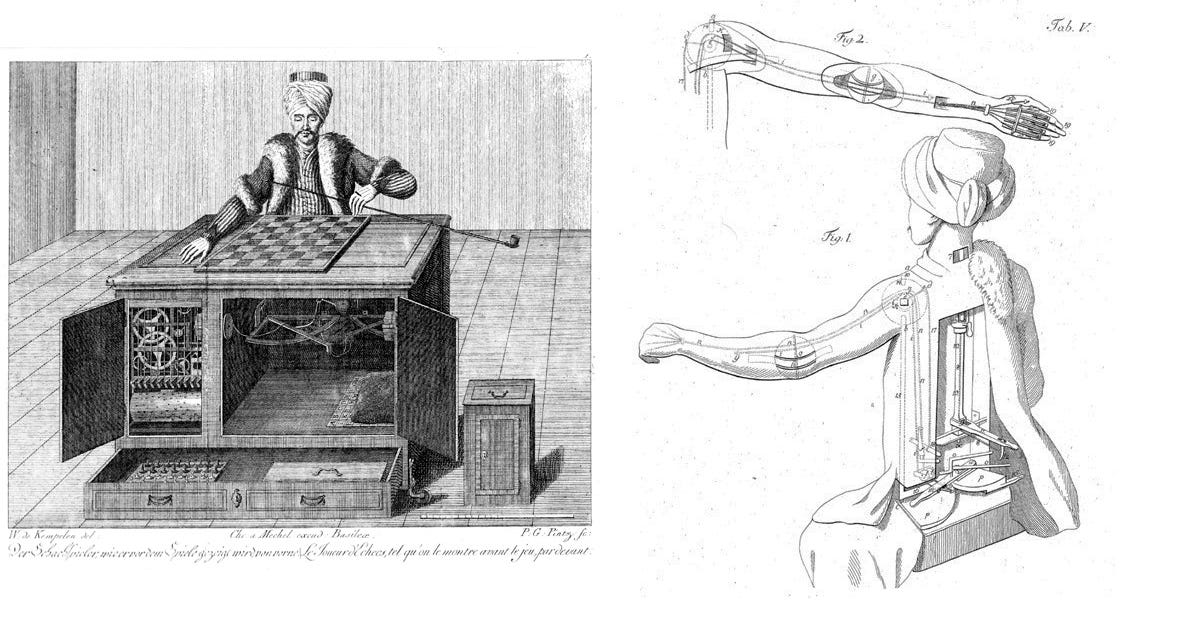

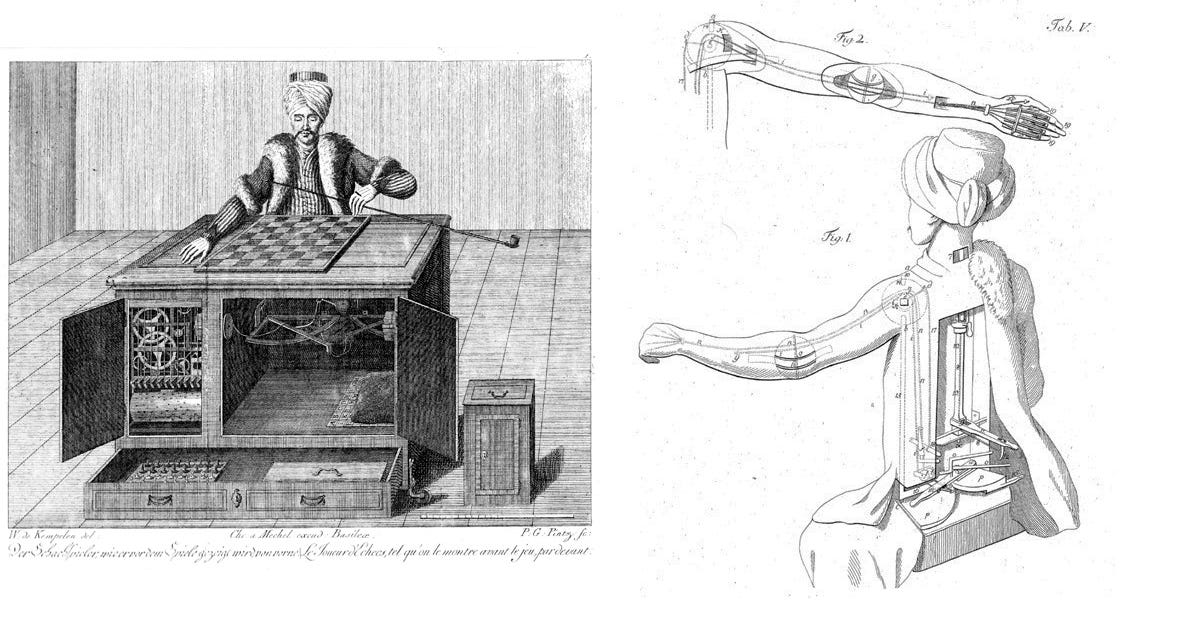

In the late 1700s, a Hungarian inventor built what appeared to be a chess-playing automaton, cloaked in Ottoman robes and a turban. The machine, known as the Mechanical Turk, impressed crowds and challenged opponents across Europe and the Americas. Eventually it was revealed that the Turk was not automated at all. Rather, a skilled chess player hid inside and moved the machine’s parts himself.

More than 200 years later, this machine inspired the name of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. Requesters can post small assignments, such as identifying objects in an image or translating a phrase, that workers complete in exchange for payment. These tasks help the requester complete projects such as image processing or data cleanup.

“Amazon dubs its platform ‘artificial’ artificial intelligence, like the Turk hoax, because a common use of the platform is to have people do tasks that are currently beyond the reach of AI systems,” says Chris Callison-Burch, Associate Professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science. “I have used Mechanical Turk for many, many years to create data to train AI algorithms, like natural language processing systems.”

Like the chess-playing machine, the work appears automated from the outside but inside, humans are doing the labor.

Media outlets have criticized the Amazon platform for allowing its requesters to pay very low wages. One task, for instance, shows workers a photo of a used envelope, and asks them to fill in the postmark location, date, and cost of the stamp. Labeling one envelope earns the worker a single cent. In one study by the Pew Research Center, 52 percent of surveyed Turk workers reported earning less than $5 per hour.

As a way of giving back to the platform he uses for research, Callison-Burch developed a Google Chrome plug-in that helps Turk workers pick out better-paying tasks. Callison-Burch and collaborators also analyzed data they gathered from the plug-in’s users to reveal trends in Turk worker earnings, published in a recent paper. The researchers wanted to address the lack of research based on quantitative data, as many studies on online worker earnings rely on self-reported numbers, which can introduce bias.

In his own work, Callison-Burch requests translations from Mechanical Turk workers, often for languages that don’t have many pre-existing translated texts in English. He then uses those translations as “training data” for algorithms that can learn how to do the translations themselves, an approach that has shaped his work.

“I really credit it with transforming the way I do research,” Callison-Burch says. “Researchers often approach machine learning problems by saying, ‘here’s an interesting data set; how do we get better results from it by building better machine learning models?’ Mechanical Turk lets me flip that around. I can first ask what problems I care about, because I know I can get the data to solve them.”

Despite its value, the online platform presents an ethical mire because workers often make abysmally low wages. Though the average requester pays over $11 an hour, Callison-Burch says, lower-paying requesters post far more tasks. Supporters of the platform point out that workers choose to sign up and get to select which tasks they want to complete. Some say that this makes the situation fair.

“However, in a functioning marketplace, people are supposed to be ‘rational actors,’” Callison-Burch says.

This means that workers should make decisions that will bring in the largest earnings. Workers can only do this, though, if they have enough information to make educated decisions. While Amazon does list how much each task pays, and provides an upper limit for how long the task should take, these two figures do not always give an accurate picture of the effective hourly rate.

To provide workers with more information, Callison-Burch built a Chrome extension called Crowd Workers. Mechanical Turk workers can download the extension and use it to track their activity on the Turk platform. It logs what time workers start a task, when they finish, and how much they were paid.

From the data Crowd Workers gathers from all its users, it computes effective hourly rates for Turk tasks. It displays these rates on the Crowd Workers website, where users can sort through to find the kind of tasks they want.

“They can do things like filter for tasks with a minimum hourly rate of $5, or search for tasks they have the skills for, or find projects with at least one task available,” Callison-Burch says. “The goal is to give them the tools to better sort through the work available.” Crowd Workers also reports the average time each requester takes to pay in order to help workers find more reliable sources of income.

Using data gathered by Crowd Workers on 2,676 Mechanical Turk workers, Callison-Burch and collaborators analyzed earnings in a recent paper. The authors propose that an hourly wage calculation should take into consideration not just the hours and minutes spent working on a task, but also the other things that take up a worker’s time. A worker might complete a task only to have it rejected by the requester, in which case they are not paid. A worker might also work on a task for a while but not be able to finish it.

On a more basic level, it also takes time to simply find and select new tasks. One might compare this to time spent waiting for a meeting to start, or for a customer to select an order.

Ignoring these auxiliary tasks, the researchers found that the median hourly wage was $6.19 per hour, and the average was $3.18 per hour. However, taking into account those sources of unpaid time, the median wage fell to $1.77, and the average to $3.13 per hour.

“Only about 4 percent of workers earned over the U.S. federal minimum wage,” Callison-Burch says.

The research team’s hope is that with more information at their disposal, Turk workers will be able to earn higher wages more easily, helping the crowdsourcing platform become a viable way for people make money.

“Despite the low hourly rates, Mechanical Turk is a place where you really can make money online and it’s not a scam,” Callison-Burch says. “I think there’s potential for this type of labor, where the workforce is easy to join, it’s easy to manage your own time, and you can work at home. It could be an option for stay-at-home parents, for people with disabilities, or for women in countries where they aren’t always allowed to work.”

The extension is just a first step toward helping people find higher paying work, Callison-Burch says. Groups like Crowd Workers could also help make the site more accessible to people with disabilities, or create ways to recommend work to optimize wages or to help workers learn certain skills. Callison-Burch hopes the extension’s quantitative reports will complement Turk worker community websites such as Turker Nation, run by collaborator Kristy Milland.

With his collaborator Abi Adams of Oxford University, Callison-Burch is also working on a follow-up study that analyzes workers’ demographics alongside their earnings.

“We’re also working on a proposal for providing crowdsourcing work and training to people in West Virginia who are unemployed,” Callison-Burch says. “Our team’s goal is to make crowdsourcing work better for the workers, and the plug-in is the first step.”