Hidden within our bones, marrow sustains life by producing billions of blood cells daily, from oxygen-carrying red cells to immune-boosting white cells. This vital function is often disrupted in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation, which can damage the marrow and lead to dangerously low white cell counts, leaving patients vulnerable to infection.

Now, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science (Penn Engineering), Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM) and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have developed a platform that emulates human marrow’s native environment. This breakthrough addresses a critical need in medical science, as animal studies often fail to fully replicate the complexities of human marrow.

Mimicking Human Marrow

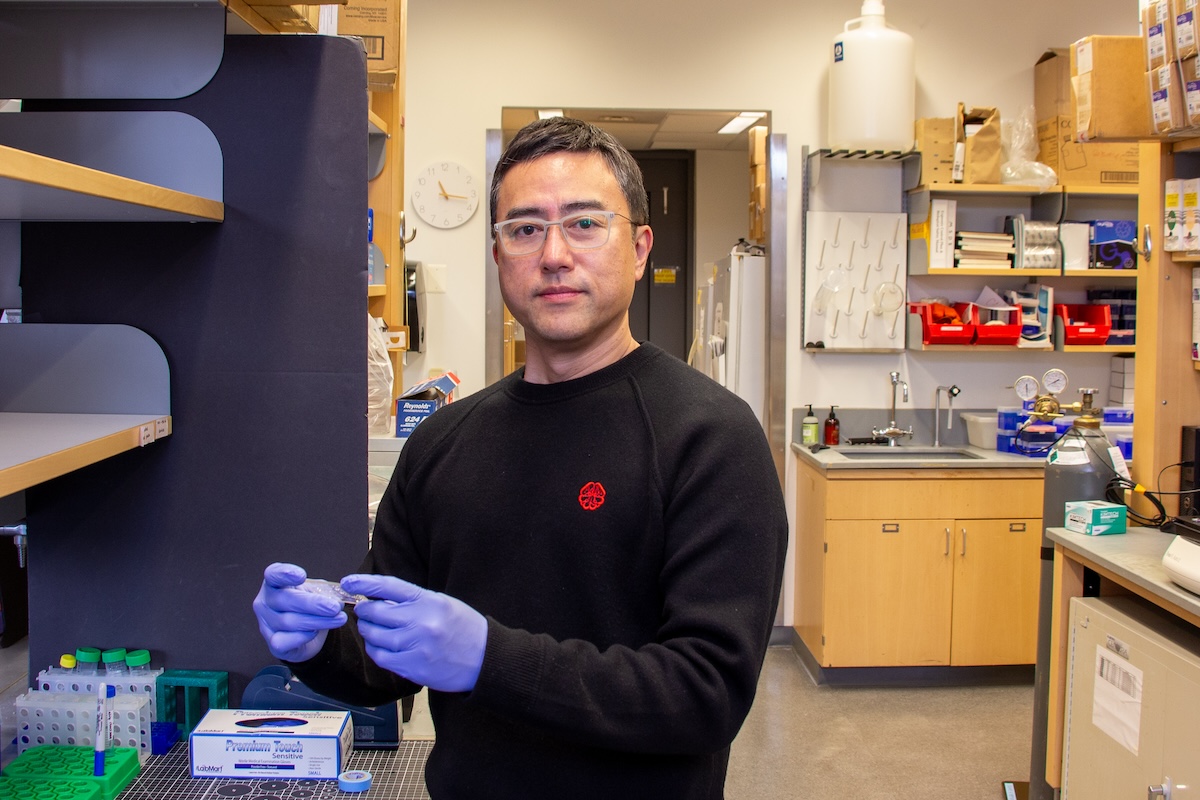

The team’s new device is a small plastic chip whose specially designed chambers are filled with human blood stem cells and the surrounding support cells with which they interact in a hydrogel to mimic the intricate process of bone marrow development in the human embryo. This biologically inspired platform makes it possible to build living human marrow tissue that can generate functional human blood cells and release them into culture media flowing in engineered capillary blood vessels.

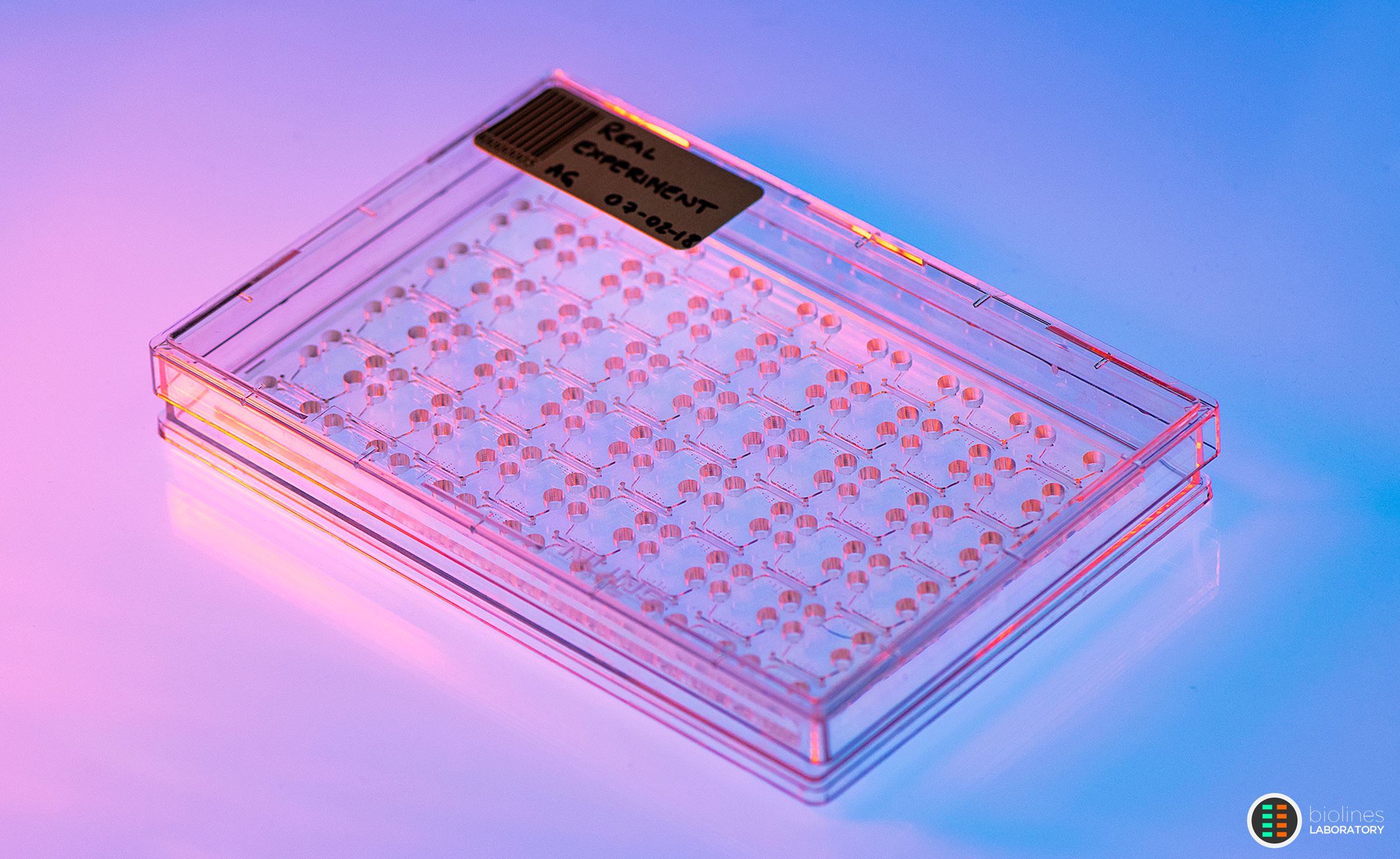

The bone marrow-on-a-chip allows researchers to simulate and study common side effects of medical treatments, such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy for cancer patients. When connected to another device, it can even model how the bone marrow communicates with other organs, like the lungs, to protect them from infections and other potentially life-threatening conditions.

Described in a new paper in Cell Stem Cell, the bone marrow model and the demonstration of its large-scale production and automation could advance fields as diverse as drug development by enabling automated, high-throughput preclinical screening of marrow toxicity of anticancer drugs) and space travel (by allowing researchers to study the effects of prolonged radiation exposure and microgravity on the immune system of astronauts).

“We’ve come a long way in terms of our ability to regenerate human tissues in vitro and mimic their complex functions, but I would say this system is probably one of the most sophisticated bioengineered tissue models developed to date,” says Dan Huh, Professor in Bioengineering and the paper’s senior author. “For example, we show for the first time in this paper the feasibility of creating interconnected organ-on-a-chip models of the human marrow and bacteria-infected lungs to emulate the biochemical crosstalk between the two organs and the entire process of innate immune response to infection, from rapid release of a large number of white blood cells from the marrow into the bloodstream to their trafficking into the infected airways where they fight off infection by engulfing the bacterial cells.”

Extraterrestrial Origins

The project originally began with the goal of studying the immune system in space. Nearly a decade ago, Huh and G. Scott Worthen, an attending physician at CHOP, Professor Emeritus in Pediatrics at PSOM and the paper’s other senior author, proposed developing a model of human bone marrow and sending it to the International Space Station (ISS). “Based on accumulating evidence showing increased risk of infection in astronauts on prolonged missions, we wanted to study how weightlessness affects our immune system,” says Worthen. “Our hypothesis was that microgravity might have adverse effects.”

Unfortunately, the researchers never had the chance to conduct paired experiments — some on earth, and others on the ISS — whose results they could compare. “Much to our disappointment, the flow controller of the cubelab system required to sustain our engineered tissue models short-circuited during ascent,” recalls Huh. “And the second launch was canceled due to the pandemic.”

Still, the new chip turned out to have a wealth of uses. “Despite the failure of our proposed space experiments, working on this project has been one of the most rewarding experiences in my research career. I find it truly exciting that by using this system, we are now able to emulate some of the most essential features of the human marrow and our immune system. I believe this new technology represents a major advance that will open many doors for us as we continue our efforts to probe, understand and modulate the inner workings of human hematopoiesis and innate immunity,” says Huh.

Borrowing Nature’s Recipe

Bone marrow is made of several main ingredients. These include hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which differentiate into the many types of cells in human blood; endothelial cells, which make up the walls of blood vessels; and mesenchymal cells, which build and maintain the connective tissue of the marrow

In the past, researchers tried combining these ingredients, but struggled to replicate the structure and behavior of actual human marrow. “All organs in the human body are complex, but the anatomical inaccessibility and unique biological intricacies of human bone marrow has made it a daunting task to model and study its physiology in vitro,” says Huh.

The key breakthrough was to focus on replicating how human embryos develop bone marrow. In utero, bone marrow growth involves multiple, overlapping processes, driven by a handful of key cell types, which “self-organize” in response to environmental signals, ultimately forming colonies of stem cells in a dense network of blood vessels that carry new cells to the rest of the body.

Figuring out exactly how to culture the necessary cell types fell to Andrei Georgescu (GEng’21), a former doctoral student in Huh’s lab who now serves as CEO of Vivodyne, the startup he and Huh co-founded to commercialize organ-on-a-chip technology. “The design principle we demonstrate in this paper is unique and different from conventional approaches in that it relies on the ability of stem and progenitor cells to self-organize and self-assemble into complex tissues,” says Georgescu. “In other words, when grown in the ‘right’ environment, those cells can build themselves into realistic tissues with physiological properties. As is often the case, finding such conditions required a lot of work.”

Towards the Holy Grail of Cell Therapy

Among the key findings of this work was that the marrow chip not only can produce blood cells but also provides an environment conducive to maintaining hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells for extended periods. This means that the chip could potentially help researchers understand the biological signals and conditions necessary to maintain or even expand hematopoietic stem cells isolated from human donors through costly, invasive medical procedures. “Given the clinical significance of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treating various disorders, exploring the utility of our technology for HSC-based cell therapies will be an important goal of our future work,” says Huh.

This study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science and supported by the National Institutes of Health (1DP2HL127720-01 and 1UG3TR002198-01); the National Science Foundation (CMMI:15-48571); the Paul G. Allen Foundation; the GRDC Cooperative Hub (RS-2023-00259341) through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT; the Bio Industrial Technology Development Program (20018463) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy; the University of Pennsylvania; and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001879).

Additional co-authors include Samira Mehta, Pouria Fattahi, Anni Wang, Sezin Aday Aydin and Jeongyun Seo of Penn Engineering; Joseph Hai Oved of CHOP and PSOM; Jonathan H. Galarraga and Thomas Cantrell of Vivodyne; Brian M. Dulmovits and Timothy S. Olson of CHOP; Pelin L. Candarlioglu, Asli Muvaffak and Anthony Lynch of GlaxoSmithKline; and Michele M. Kim and Eric S. Diffenderfer of PSOM.