In Lewis Carrol’s “Through the Looking Glass,” protagonist Alice races with the Red Queen and is unable to gain a lead despite her best efforts. “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!” the Queen yelled.

Biologists have co-opted this story to explain why organisms need to constantly adapt in the evolutionary race for survival—dubbing it the Red Queen Hypothesis. And though this analogy has been used most commonly in the context of parasite-host interactions, it also captures the ongoing battle between cancer treatments and tumor evolution: Each time researchers develop a powerful new therapy, tumors evolve new ways to evade, resist, or neutralize it.

Now, a cross-disciplinary team at the University of Pennsylvania has identified a striking example of such biological ingenuity and a way to fight back. Led by Wei Guo of the School of Arts & Sciences, the researchers revealed a mechanism by which solid tumors sabotage chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy by turning the body’s own immune warriors against each other. Their findings are published in Nature Cancer.

“This is one of the more insidious ways solid tumors evade immune attack,” Guo says. “The field had seen CAR T cell fratricide before, but this is the first time we’re seeing that it can happen remotely—through signaling molecules—without direct cell-to-cell contact.”

CAR T cells are genetically engineered to seek out and destroy cancer cells by recognizing specific tumor antigens. Guo explains that they’ve shown “great success against blood cancers, but for solid tumors like in pancreatic cancer, progress has been limited.”

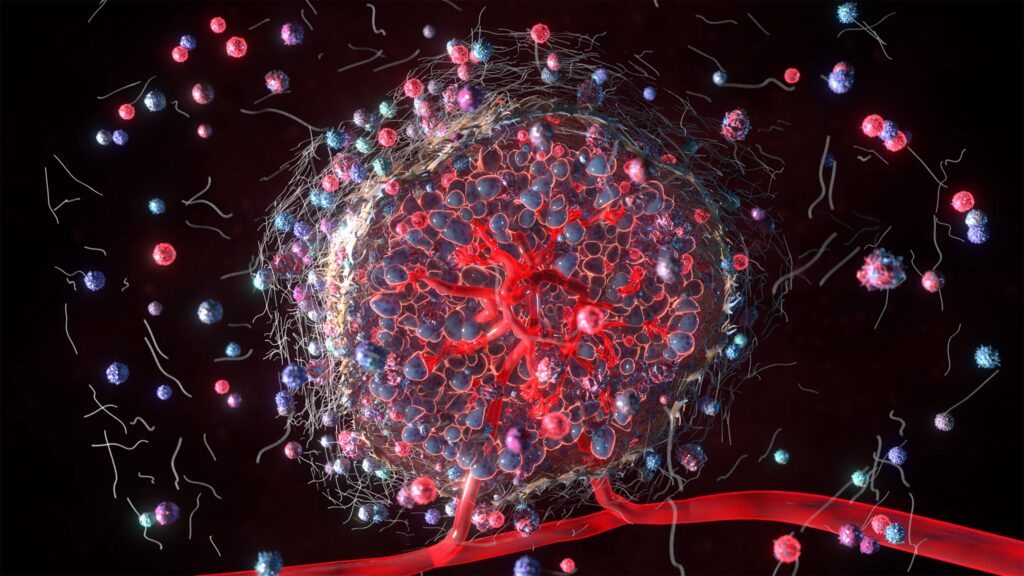

The researchers had previously discovered that solid tumors release small extracellular vesicles (sEVs)—tiny, lipid membrane-bound packages that ferry cargo between cells, including those that are loaded with tumor antigens. When CAR T cells engulf these vesicles, they absorb the tumor markers onto their own surfaces, Guo explains. As a result, other CAR T cells mistake their fellow cancer fighters for cancer cells, launching fatal attacks. This misidentification leads to fratricide and drastically reduces the efficacy of the therapy.