When asked “why study robots?” Antonio Loquercio, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering, says that he himself is 10% robot. Diagnosed with diabetes when he was four years old, Loquercio has relied on a continuous blood glucose monitor and pump to track his blood sugar levels and administer insulin throughout the day for most of his life. This machine that senses its environment and responds accordingly fits into Loquercio’s definition of a robot, a definition that he has been applying to his own research questions for the last six years. And while Loquercio wants to help design and build robots that can be used to solve real-world problems, such as removing barriers for people with chronic diseases, safely doing household chores and assisting in surgeries, he resonates even more with the potential robots have in answering fundamental questions on decision making and what it means to be intelligent.

When asked “why study robots?” Antonio Loquercio, Assistant Professor in Electrical and Systems Engineering, says that he himself is 10% robot. Diagnosed with diabetes when he was four years old, Loquercio has relied on a continuous blood glucose monitor and pump to track his blood sugar levels and administer insulin throughout the day for most of his life. This machine that senses its environment and responds accordingly fits into Loquercio’s definition of a robot, a definition that he has been applying to his own research questions for the last six years. And while Loquercio wants to help design and build robots that can be used to solve real-world problems, such as removing barriers for people with chronic diseases, safely doing household chores and assisting in surgeries, he resonates even more with the potential robots have in answering fundamental questions on decision making and what it means to be intelligent.

Loquercio’s passion for robotics stems from his childhood curiosity and lifelong love of nature. Spending afternoons outdoors in Capranica, a small town outside of Rome, Italy, the young scientist would watch ants marching in line, birds building intricate nests and schooling fish moving as one.

“I was always fascinated with the way animals carry out specific tasks,” says Loquercio. “I wanted to know how and why they chose to perform those tasks over others and how they were picking up on cues from the environment to help make those decisions.”

That same question stayed with him as he made his way through his bachelor’s program and began his research career at the University of Zurich.

“Studying the decision-making process in animals is very complex and there are many uncontrollable variables,” says Loquercio. “By building a separate robotic system, we can examine those questions at much higher granularity and study every level of decision making. This was what I started to explore in my Ph.D. through a very ambitious task: building the fastest drone possible.”

Loquercio’s work in graduate school showed him how drones, a specific type of flying robot, would interact with their environment when provided with only limited sensing and computation. They’d have to make decisions based on wind speed, the location of trees and buildings in 3D space, and have to make these decisions very quickly.

Loquercio’s work in graduate school showed him how drones, a specific type of flying robot, would interact with their environment when provided with only limited sensing and computation. They’d have to make decisions based on wind speed, the location of trees and buildings in 3D space, and have to make these decisions very quickly.

“I got into drone racing during my Ph.D.,” says Loquercio. “Not because I loved racing, but because it was an environment where I could push the robots’ abilities to the limits. A real-world, complex environment provides data from many sources, and successfully interacting with it requires a certain kind of intelligence. As humans, we learn how to interact in 3D space as well as how to collaborate and interact with other humans quickly and successfully, even with a limited set of information from our environment. This type of intelligence, what we might refer to as common sense, is something current robots aren’t fluent in yet. In my Ph.D., I dove into teaching robots the ability to assess surroundings and make informed decisions without having all the data possible, and have continued to do so in my work since.”

Teaching common sense to robots is no easy feat. At Penn Engineering, Loquercio is working to accomplish this goal through specific projects that aim to teach robots to walk, run and jump through different terrain while adapting to changes in their environment. He is also working on teaching robots to learn behaviors by imitating humans and teaching robots to make informed decisions with a limited set of prior information. But he won’t stop there. Once he accomplishes all that, Loquercio sees a clear next step in advancing robots to a point where they will truly be helpful in our everyday lives.

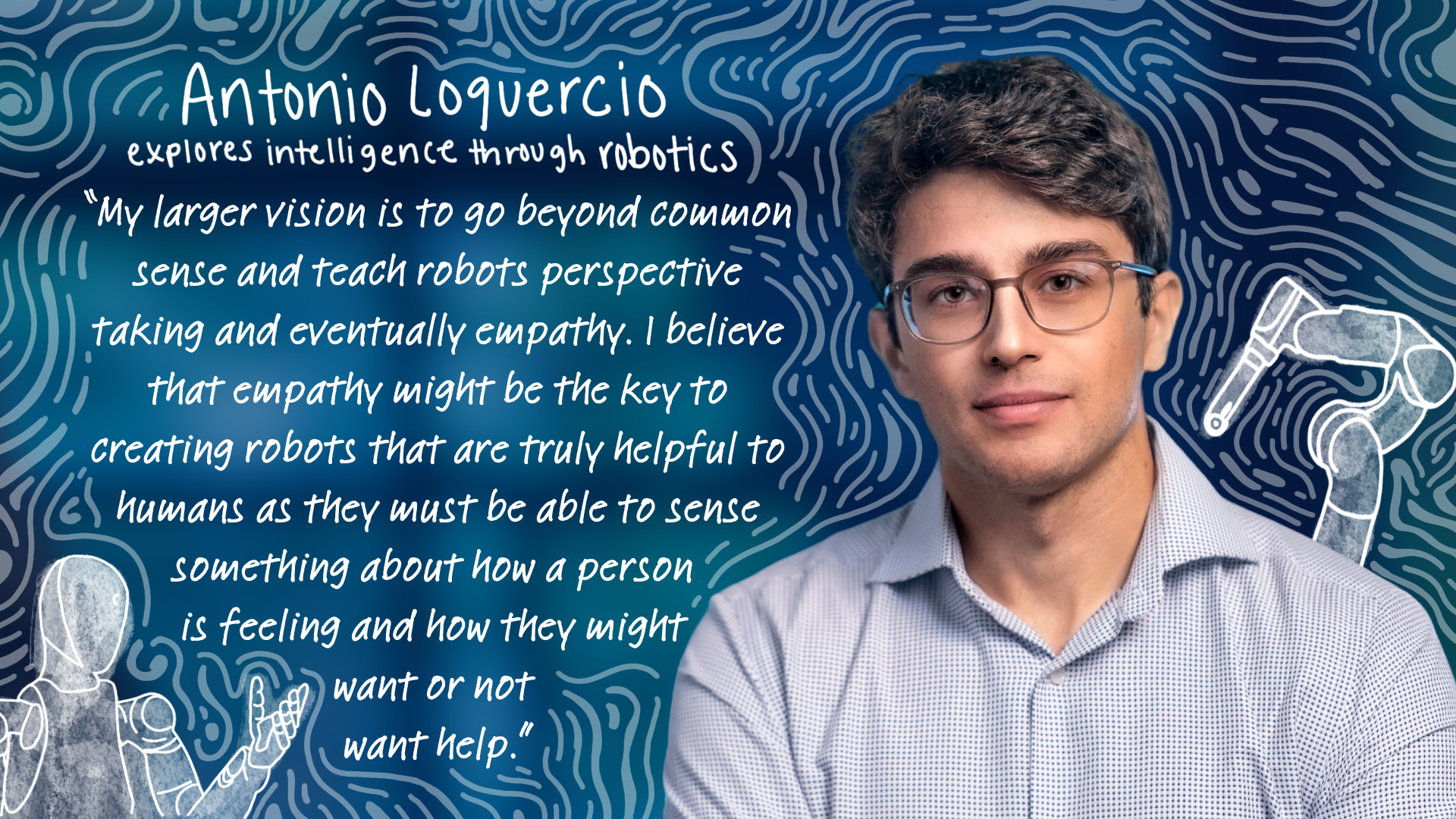

“Through science fiction books and TV shows like The Jetsons, we once envisioned a 21st century with machines and robotic technology intelligent and dexterous enough to take over tedious or physically demanding tasks,” he says. “However, as we have started using today’s technology, the roles have been reversed. Now Chat GPT is being used to do the more creative work like writing and making art, and we are left doing the household chores. My larger vision is to go beyond common sense and teach robots perspective-taking and eventually empathy. I believe that teaching robots empathy might be the key to flipping the roles around, because, for robots to be truly helpful to humans, they must be able to sense something about how a person is feeling and how they might want or not want help.”

A robot that can successfully navigate its 3D environment, make informed decisions with a limited set of data and understand when a human needs help could very well look and function like the helpful housekeeper robot, Rosey on The Jetsons. As a member of the Penn Engineering faculty, Loquercio is in a unique position to advance robotics to a point where chores and physical tasks as well as precise monitoring of a person’s health can be done reliably by machines.

“The only way we are going to be able to build humanoids that safely and accurately interact with humans or robots that continuously and precisely monitor and administer personalized therapy to people in need is through collaboration,” says Loquercio. “This is the main reason I chose to come to Penn. Penn’s history of robotics has included and continues to recruit expert faculty from many different disciplines that are all trying to build robots that augment the human experience, not compete with it. I am excited to fit into the puzzle of robotics here and work with other researchers on all different kinds of problems.”

As Loquercio starts his Penn Engineering career, he is also looking forward to working with the next generation of roboticists. To support and encourage future students in his lab to dream big, Loquercio is establishing a strong mentor-mentee culture and is currently building out his lab on the fourth floor of the Levine Building with the intent to provide a space where students can freely and safely explore their ideas.

“Your Ph.D. is one of the few times in your life that allows you to take big risks,” says Loquercio. “If you take a big risk and succeed, you have the potential to change your life and others with your work. If you don’t succeed, you’ll still leave with a Ph.D. in engineering, which is an amazing feat in and of itself. I want to work with people who are not afraid of looking into the unknown and jumping into it.”

Learn more about the work and collaboration opportunities in the Antonio Loquercio lab by visiting his website.