A young girl watches her father tinker with two piston rings in his neatly organized workshop, where everything has its place. He uses his fingers to assess the shape, weight and balance of the technology, which, through his own innovative improvements, helped to propel the automobile industry from horse and buggy to Indy 500 race cars. His later inventions would lay the groundwork for self-driving cars. But in 1941, Marjorie, aged 10, had only just learned her father, Ralph Teetor, was completely blind. Her perception of him doesn’t change: He has always been able to see what the world needs.

The Boy Who Refused To Stop Building

Born in Hagerstown, Indiana in 1890, a curious five-year-old Ralph Teetor was naturally drawn to his uncles’ work in manufacturing railroad inspection cars. Stepping into their machine shop on a day like any other, young Teetor tried to pry open a drawer with a knife, lost control and injured his eye. This traumatic moment took the sight from one eye and eventually led to the loss of sight in the other, leaving him completely blind by the age of six. However, it was that fateful injury that gave Teetor the superpowers key to his career, his inventions and the ways he’d give back to his community.

As he began to navigate the world around him without sight, he harnessed other senses that became so heightened, many people would forget or never know he was blind.

At 12 years old, Teetor and his cousin handcrafted their very own gasoline-powered vehicle that, while noisy due to its iron wheels and lack of a muffler, was a feat for boys of their age. Moving at the lightning speed of 12 miles per hour, his first invention propelled him into the next. In high school, he created Hagerstown’s first electric sign for his high school graduation.

An Unlikely Acceptance

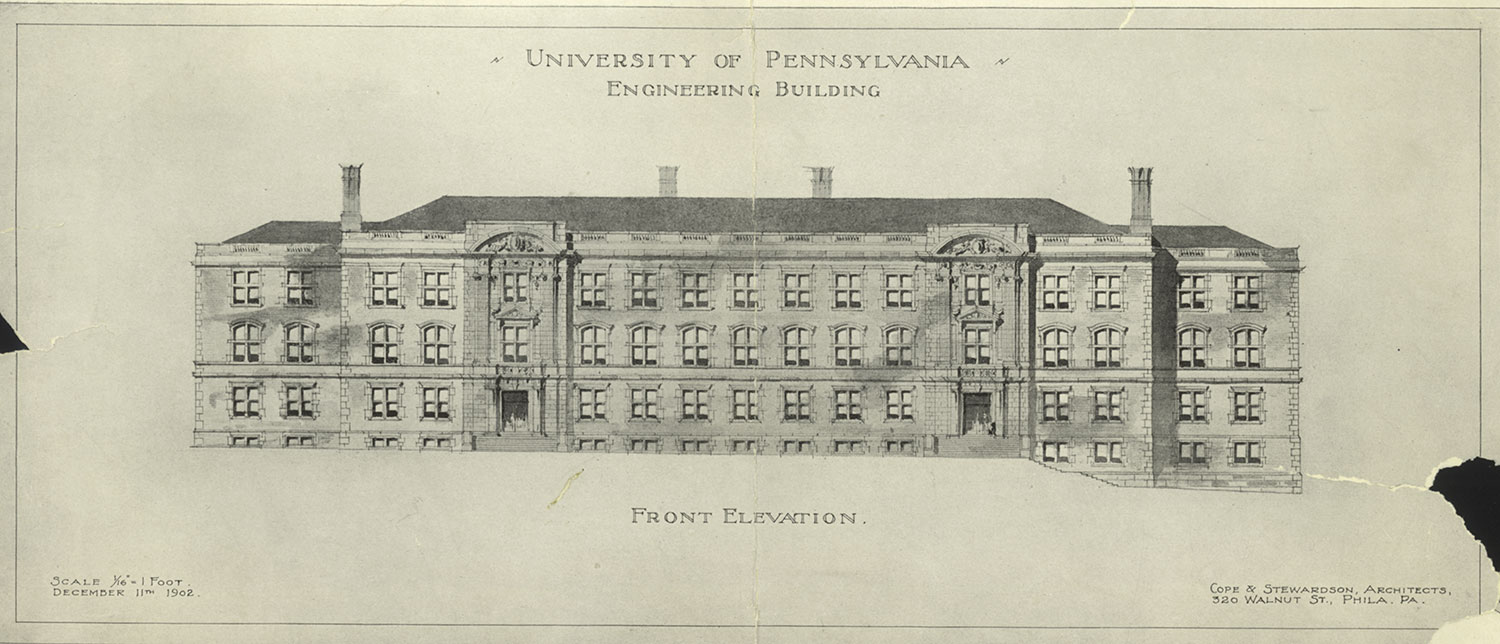

Hoping to turn his passion into a career, Teetor wanted to attend university, but his attempts to pursue a formal education were not encouraged by others with the same gusto. Teetor was rejected by the University of Michigan due to his disability, but he did not give up, applying to the University of Pennsylvania with the help of a cousin.

“Grandpa took a train to Philadelphia with a year’s worth of clothes in his suitcase, maybe a little naively optimistic that Penn would give him a chance,” says Teetor’s grandson, Ralph Meyer. “He spoke with the dean directly, who permitted him to join the incoming class. He thought it best that Ralph discover his capabilities without being told by other people.”

Despite these initial concerns, Teetor excelled at Penn and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering in 1912, making history as one of the first blind graduates at Penn and the first blind engineer in the United States.

“Ralph’s success hinged on the University giving him that chance, even though many had their doubts,” says Jack Teetor, Ralph Teetor’s great-nephew. “His persistence and passion saw him through earning his first degree and later a master’s degree at Penn, which he received in 1930.”

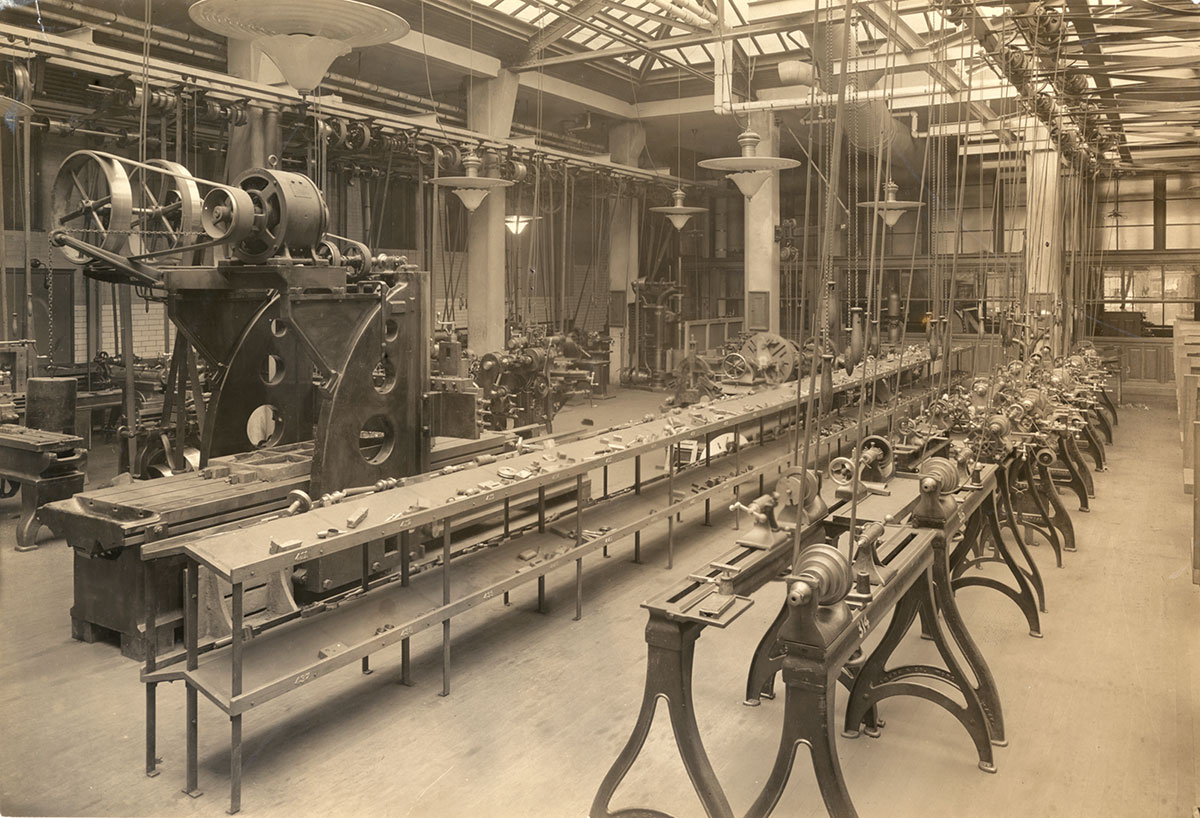

Engineering What He Couldn’t See

With his first degree under his belt and decades of experience seeing with his hands, Teetor returned to Indiana and joined the family business, manufacturing internal combustion engines and piston rings for the automobile industry. Entering the Roaring Twenties, the industry was turning to assembly-line manufacturing. As their engines were hand-built and not set up for assembly-line production, Teetor recognized a strategic shift and positioned the Teetor-Hartley Motor Company as a powerhouse for manufacturing their superior, oil-regulating piston rings which were designed to apply uniform pressure against the cylinder wall for better oil regulation and engine performance.

This direction led Teetor to co-found Perfect Circle, a family-owned business in automobile parts manufacturing, with his piston ring becoming the gold standard for all makes of cars, particularly race cars that required perfectly balanced engines to sustain speeds of 120 miles per hour and above.

The piston ring was a game changer for Teetor’s career as well as those in his community. It was Perfect Circle’s piston rings that kept Hagerstown a town of prosperity throughout the Great Depression: New car sales plummeted, but car owners still needed to maintain their vehicles. Teetor’s piston rings were shipped out to repair shops across the country and the employees of Perfect Circle, now a majority of the town’s population, were able to maintain their quality of life in otherwise trying times.

Cruising Into the Future

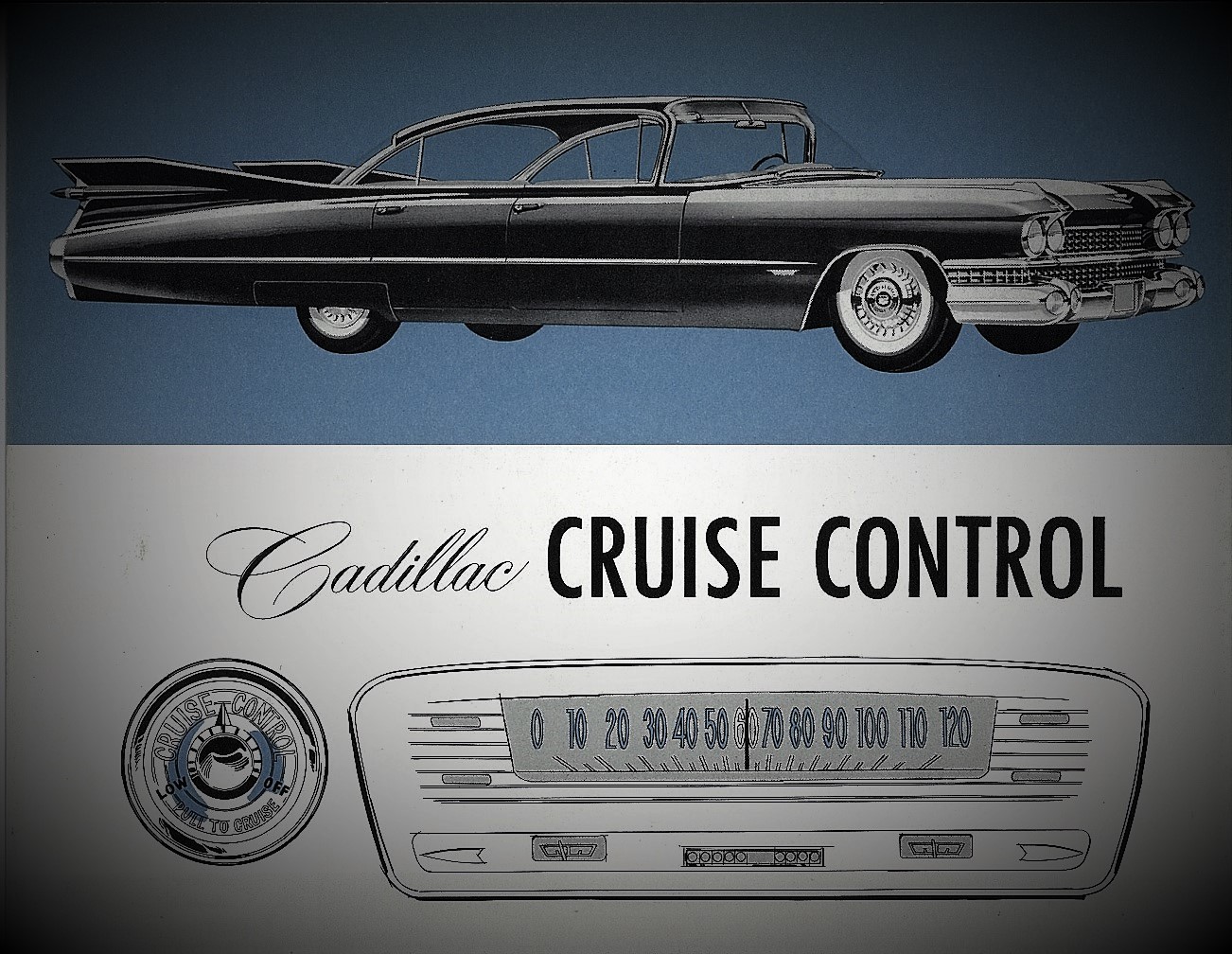

Soon after the company’s piston ring success, Teetor was on to the next invention. He created the fluid-operated gearshift in the 1920s and piston ring expanders in the early 1930s, but by the end of the decade, he had come up with an idea that would lead to his most significant invention. Inspired by his experience as a passenger in a car with his long-time friend, Teetor’s idea for the Speedostat, the first cruise-control device, was born.

“My grandfather’s dear friend and patent attorney, Harry Lindsey, was the jerkiest throttle-brake driver he ever knew,” says Meyer. “This so annoyed grandpa that for 10 years, he considered how to invent a speed-control device for drivers like Harry. It occurred to him that such a device would also improve gasoline economy and automobile safety.”

In 1950, Teetor’s Speedostat, a device that allowed a driver to maintain a constant speed without having to manually press the accelerator, was patented and on the market. While it was originally seen as a luxury, the Speedostat was soon adopted by Chrysler in 1958 and then by Cadillac, first marketed as “auto pilot” and finally cruise control, as it is known today. Over time, most makes and models came to adopt the technology, and Teetor’s invention set up the automobile industry’s launch into the future. Today, many consider cruise control to be a key prerequisite technology for autonomous vehicles.

‘No One Is Handicapped If They Can Think’

Ralph Teetor used Perfect Circle as a force for community care and stability. During the Great Depression, the company vowed to not lay off employees and hired those who had lost jobs elsewhere. As company president, Teetor fostered equity and dignity, especially for war veterans, telling them “You are not handicapped so long as you can think logically. People have told me how sorry they were that I am handicapped. My answer to them has always been that I am not handicapped because I have never considered myself so. It will take courage and hard work for you to become accustomed to your new way of life, but you will make it by holding your heads high and never allowing yourself to falter.”

Preserving Teetor’s Legacy

While at Penn, Teetor was a part of the Whitney Engineering Society and served as the mechanical editor of its magazine. He also authored two articles, “The Use of the Manograph Indicator” and “The High-Speed Internal Combustion Motor.”

Teetor’s legacy was highlighted at Penn in 1975, when he was the first graduate to be recognized as a Penn Engineering distinguished alumnus. Each year, undergraduates in Penn Engineering continue to honor Teetor’s legacy through the presentation of the Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics (MEAM) Ralph Teetor Award, established by MEAM and awarded to a senior who has demonstrated the qualities of ingenuity, creativity, scholarship and service.

“The qualities that Ralph Teetor possessed throughout his life and career are deeply ingrained in Penn’s ethos,” says Igor Bargatin, Associate Professor and Undergraduate Chair of MEAM. “What’s even more impressive than his ability to overcome the challenges he faced was his commitment to improving the quality of life of people around him. The students who receive the Ralph Teetor Award are not just chosen based on merit and scholarship, they are selected due to their passion and work dedicated to serving others in their class, field and community.”

Beyond Penn, Teetor’s influence in the world of automotive engineering extends to the Society of Automotive Engineers, where the Ralph Teetor Educational Fund was established to support early-career professors across the nation to bridge industry and academia.

Blind Logic: The Story Told Anew

Ralph Teetor passed away in 1982, with 50 patents, an induction into the Automotive Hall of Fame and a larger-than-life legacy. His story resonates with today’s engineers and tomorrow’s problem solvers facing challenges that require perseverance and passion.

“Ralph Teetor is a person this country needs to know,” said Mike Rowe, narrator of the film Blind Logic.

Blind Logic is a biographical documentary made by Teetor’s great-nephew Jack Teetor over the course of 11 years. Support in the making of the film was done in true Teetor fashion — a collaborative effort from many family members. Teetor’s grandson Ralph Meyer, along with Dan Teetor, Jack Teetor’s brother and photo editor, as well as their cousin and music composer, Jim Andron, contributed to the film.

“We wanted to bring forward this extraordinary, untold story of one of America’s most remarkable automotive pioneers and inspire generations to come,” says Jack Teetor. “My hope is that today’s engineering students are motivated by what Ralph achieved as both an engineer and as a person, and that they carry forward the same qualities that defined his life: concentration, logic and strong mental vision. Throughout the filmmaking process, I was constantly inspired by Ralph’s remarkable character and I can honestly say I became a better person because of it.”

Ralph Teetor may not have seen the road ahead, but he made sure the rest of us could travel it more smoothly.

Stream Blind Logic on Apple TV, Amazon Prime, Google Play, Hoopla and select cable providers.