Close your eyes. What do you see when you imagine the future? Is it a haven of ecologically sustainable technologies and AI assistance? Is it a nightmare of autonomous machines gone rogue? Is it even possible to imagine with clarity from this point in time? These are the questions posed by Designs for Different Futures, a new exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that contemplates what our daily lives may look, feel, smell and taste like in the not-so-distant future, with contributions to the show from Penn Engineering faculty, students and alumni.

Humans have speculated about the advances that the next generation of technology will bring since the first stone tools were built. Often, the topic is a source of anxiety. While science-fiction novels convey angst over the potential of flying cars or mutant vaccines, there are real concerns about the longevity of civilization as we know it. Will there be enough food for the next hundred years’ worth of population growth? Will rising carbon dioxide emissions render the planet uninhabitable? Will advances in humanoid robotics help or harm our social interactions? Designs for Different Futures takes up these questions and creates an innovative program of experiences for museum guests that leans into the speculative and explores the unknown.

While this show has been six years in the making by curators at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Penn Engineering was integral to its conception. Back in 2013, lead curator Kathryn Hiesinger spoke to Mark Yim, now the newly appointed director of Penn Engineering’s GRASP Lab and Asa Whitney Professor in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics (MEAM), as well as Simon Kim, associate professor of Design in Penn’s Weitzman School of Design. The three met through the Integrated Product Design program at Penn, an innovative graduate program that brings together Penn Engineering, the Stuart Weitzman School of Design and the Wharton School to design cutting-edge products centered on consumers.

“Kathryn asked about different things that we had done, and Simon and I had done a bunch of these engineering and art projects through IPD classes,” Yim says. “As we talked about the items we produced, Kathryn thought many of them could go well in her upcoming show.” It’s no wonder that Hiesinger, Kim and Yim came together to formulate this show as the worlds of art and robotics are becoming increasingly collaborative disciplines.

“In the courses we teach,” Kim says, “students from different academic backgrounds come together to learn from one another. Engineers learn from architects, architects learn from business students and so on. It’s a collaborative exercise that produces work that could not be realized if the students remained locked away in their respective fields.”

Yim adds that art classes for engineers are a crucial component of the IPD program at Penn because it boosts the students’ problem-solving creativity.

“Art and robotics are coming together,” Yim says, citing the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) inclusion of the ICRA-X Robotic Art Forum within its program. This forum was the first of its kind to offer “a central space to art” that intended to “address the importance of artistic contributions to the field of robotics research, and to its social and cultural impacts.”

As the art and robotics worlds collide, this collaboration across disciplines for Designs for Different Futures makes sense: Good design seeks to solve problems, and good engineering does the same thing. Several pieces from Penn Engineering faculty and alumni are featured in the show, including Lia, the first FDA-approved flushable pregnancy test; Allevi 3D Bioprinters, which use “bioinks” to create synthetic human organs in the lab; B| reactor Incubator, a compact device for growing tissue; and the Ghost Minitaur, a four-legged, multi-terrain robot.

Designs for Different Futures is organized into eleven different sections: Resources, Generations, Earths, Bodies, Intimacies, Foods, Jobs, Cities, Materials, Power and Data. Pieces in the show range from a fifteen-foot inflatable pod that expands and contracts in response to carbon dioxide levels in the room, to a cricket shelter insect farm meant to provide a sustainable protein-rich food source, to robotic exoskeletons that aid individuals with limited range of motion. In addition to the wide-ranging exhibit, curators collaborated with the museum’s Education Department to create the Futures Therapy Lab, a welcoming, bean-bag-filled room that features art-making stations, a library of comics, science fiction and children’s’ books, bean bags and a “talk-back” wall where guests are invited to write their visions for the future on index cards and hang them up for others to consider. Thinking about the future on this scale can be overwhelming, and curators felt that it was important to provide a space for museum guests to process the exhibit in whatever way they choose.

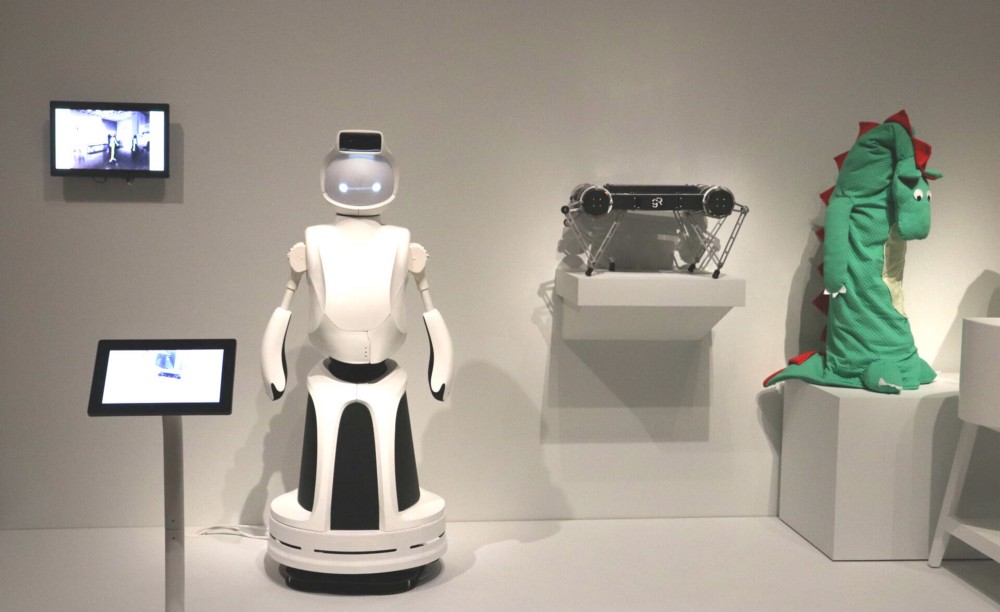

Yim and Kim’s own work of robotics-as-art is featured in Designs for Different Futures: Quori, an affordable, socially interactive robot used for human-robot interaction (HRI) research. Quori was developed by a team of seventeen students at Penn, under Yim and Kim’s direction. It is featured in the Jobs section of the exhibit alongside the Ghost Robotics Minitaur and Raising Robot Natives by Phillip Schmitt, an artistic tableau that features an industrial robotic arm holding a baby bottle. Guests can interact with Quori by moving around in front of it, activating its sensors and watching the robot respond to human movement.

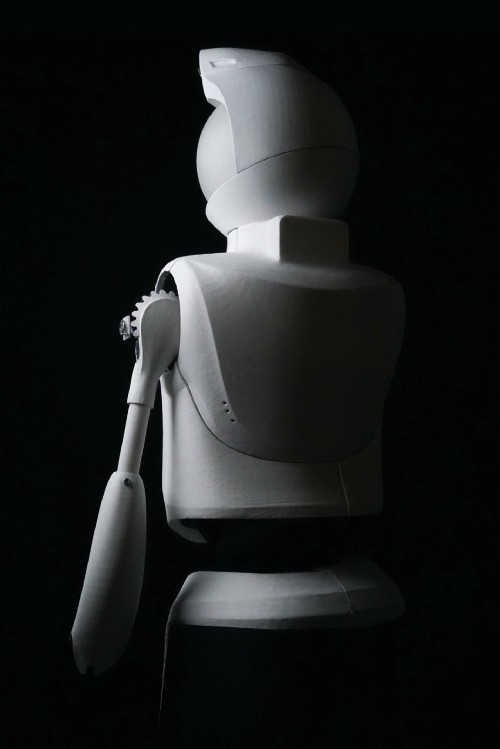

In terms of design, Quori stands at about five feet tall, with a customizable digital face, a broad chest, gesturing arms and an omnidirectional mobile base surrounded by a pyramid-shaped shell. Those features are supposed to be genderless, but Yim says that many researchers see Quori as female. Such interactions highlight a theme of the exhibit: the tension between intended design and a user’s perception. When encountering a never-before-seen design, users want to make it familiar and easy to understand. In Quori’s case, this means imposing gender on a genderless robot.

“Some people think it’s wearing a skirt,” Yim concedes. “Part of the reason for that skirt-like design on the bottom is that we needed space for the motors and wheels, so it couldn’t have legs. But whenever anyone looks at something, they immediately try to call it ‘him’ or ‘her.’ So that is difficult.”

Redesigning Gender

Designs for Different Futures explores the future of gender expression throughout the show, with pieces like Quori, Q, the first genderless voice assistant, and Housewives Making Drugs, a fictional cooking show where the trans-femme hosts synthesize estrogen in their home kitchen. Quori contributes to this growing discussion because as more robotics and AI are being designed for human-robot interaction, gender bias in robotics is becoming a real issue.

A 2011 study found that experiment participants responded more positively to a female-sounding voice when it was dispensing advice or assistance, and more positively to a male-sounding voice when it was giving commands or warnings. This study demonstrates that the gender biases that humans have accrued within human-to-human interactions are also pervading human-robot interactions. The danger of heavily gendered AI and robotics is the potential to reinforce harmful gender biases in our future society. A UNESCO examination of gendered AI technology warns that female-voiced AI assistants, such as Apple’s Siri and Google’s Alexa, “spread gender bias,” “model acceptance and tolerance of sexual harassment,” and “force synthetic ‘female’ voices and personality to defer questions and commands to higher (and often male) authorities.”

It is possible that designing distinctly male or female robots will further entrench gender norms in society as humanoid robots become increasingly prevalent in the workforce. The jobs robots are designed to do can be influenced by their presented gender, which impacts the human world as much as the robotic world. The solution to this problem is multifaceted, but at its core, gender expression in robots is a design issue. Designers like Yim and Kim are tasked with advancing the field beyond existing gender roles and building a new kind of robot whose capabilities are not limited by how it looks.

It matters that Quori is gender neutral because Quori is a teaching robot. Its genderlessness provides a blank slate for HRI researchers and it will hopefully help to reduce gender bias in the field when researchers investigate what jobs or roles robots could fill in the human world. Even if HRI researchers choose to dub their Quori a man or a woman, its design sends a message to other robotics designers that a humanoid gender-neutral robot is possible — and perhaps essential.

But should we be scared of advances in robotics and AI? Once outside the walls of an art exhibit, what happens when intelligent robotic technologies become part of everyday life? Scientists and consumers alike have voiced a variety of concerns, like the fear that AI will develop beyond the control of humans and learn to reprogram itself, or the exponential automation of the workforce and the eradication of jobs primarily held by low-income workers. There have already been calls for stricter regulations when it comes to AI and data privacy, and many are wary of military-based research into a new breed of autonomous “killer” robots.

“I define a robot as something that has a motor, has some sensors and has some intelligence — some way to make it move in reaction to the sensor,” Yim says. “That’s what the Roomba does. But also, your VCR did that, your cell phone does that, cars do that and microwaves do that. It’s all programming. They all have computers in them. In the future, what we call a robot now might not necessarily be what we call a robot today.”

The core technologies that are making robots more autonomous and human-like — artificial intelligence and machine learning — are perhaps the most anxiety-inducing, as they force us to reckon with the deepest social and philosophical questions that Designs for Different Futures presents. Still, Yim believes that machine learning is just another in a long line of technological tools, saving time and making life easier and more efficient.

“When people talk about machine learning,” Yim says, “they ask: ‘Is it going too fast; will we lose control of it?’. But the fact of the matter is that computers have been faster than humans for decades. And it’s not the end of the world. Yet as a society we are recognizing that machine learning could potentially be a problem and we have to make sure we’re doing the right thing.”

“And, in regards to fear,” Yim adds, “A robot is just a thing. It’s a tool. It’s useful. There’s no reason to feel afraid of it, we just need to understand how it’s being used.”

While Yim rests assured that robots are not bearers of a technological apocalypse, he does believe that robotics should seek to design for social good. Quori is one example of designing for a scientific and social purpose, a product that considers the implications of its own existence. Looking to the future, Yim believes that our world will become more automated but, ultimately, it is up to designers today to construct the world we live in tomorrow.